The use of ornament in architecture has long provided fuel for debate about architectural aesthetics. Ornament is typically defined as the elaboration of functionally complete objects for the sake of visual pleasure or cultural significance. Historically, ornament in architecture has been conceptualized as something that is an additive, unnecessary, building component applied to a host surface or object. Adolf Loos writes, “The evolution of culture is synonymous with the removal of ornament from utilitarian objects.” It is largely accepted that Modern architecture by the call to eliminate ornament from architecture in lieu of augmenting the true spatial experience produced by architectural surface, form and space. It is also often agreed upon that Post-Modern architecture took an opposing position to the use of ornamentation, utilizing it to support its desire to communicate, to reference something other than itself. Post-Modern architecture seeks exuberance and celebrates the use of ornament. In contemporary architecture, many practitioners are seeking to redefine the term, “ornament”. Rather than being viewed as additive or an applied, ornament can now be understood as an integrated, performative, functional building component, one that bears technical responsibilities such as enclosure, aperture, daylight modulation, and temperature control, as well as the aesthetic and effective considerations that augment the visual potency and overall emotive qualities of a contemporary structure, and more specifically, a contemporary building facade. Contemporary ornamentation rejects the superficial applications of previous architectural genres and simultaneously seeks the authenticity that was sought after in Modernism. In Organized Crime, there are no lies and nothing is fake.

This surface to perform (actually and virtually), the facade gains thickness and becomes volumetric. It is within this volume that there is an opportunity for complex design. It is this concept of employing multiple intrinsic qualities that embodies the performative nature of this design. Ornamentation ceases to be symbolic of something else and becomes valid in its own right as an integrated design element.

CASE STUDY – Valletta City Gate / Renzo Piano

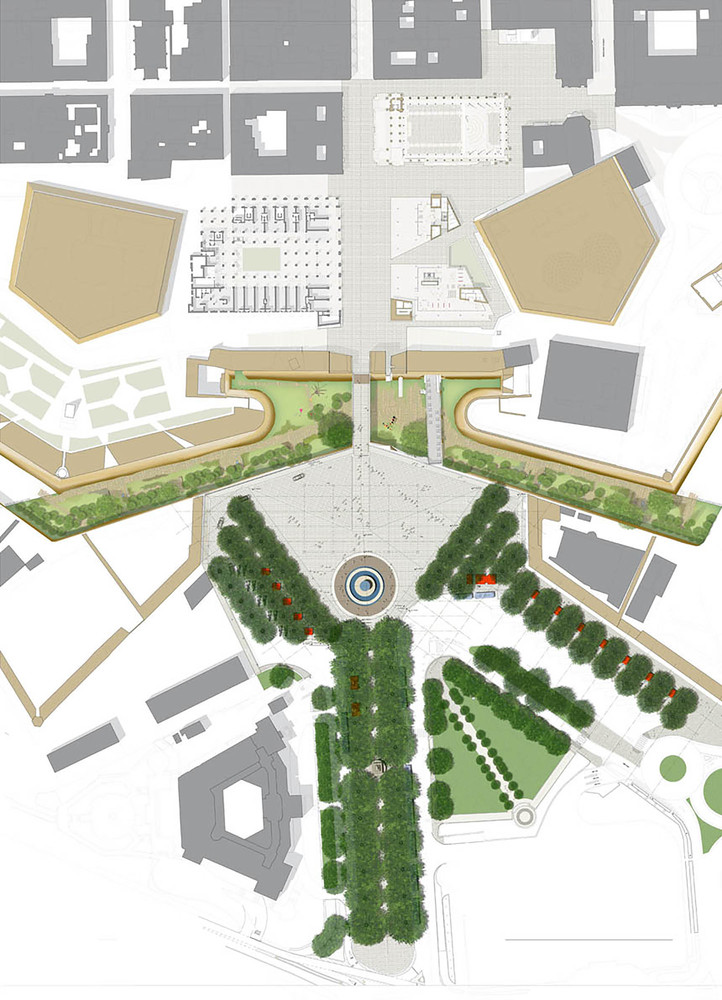

From the architect, Renzo Piao, The ‘City Gate’ project takes in the complete reorganisation of the principal entrance to the Maltese capital of Valletta. The project comprises four parts: the Valletta City Gate and its site immediately outside the city walls, the design for an open-air theater ‘machine’ within the ruins of the former Royal opera house, the construction of a new Parliament building and the landscaping of the ditch.

Architects – Renzo Piano

Location – Ordinance, Valletta, Malta

Partners in Charge – A.Belvedere, B. Plattner

Project Year – 2015

With the aim of resolving this rather unsatisfactory transformation, the project focuses on returning the bridge to its 1633 ‘Dingli’s Gate’ dimensions, by demolishing later additions. This allows passers-by to once again have the sensation of crossing a real bridge, and gives them views of the ditch and fortifications.

The first objective of the project was therefore to reinstate the ramparts’ original feeling of depth and strength and to reinforce the narrowness of the entrance to the city, while opening up views of Republic Street. The new city gate is a ‘breach’ in the wall only 8m wide. The relationship between the original fortifications and those that have been reconstructed is made clear by the insertion of powerful 60mm-thick steel ‘blades’ that slice through the wall between old and new.

The key element of this redevelopment was opening the gate to the sky. The section of Pope Pius V Street that formerly ran immediately inside the gate at a raised level has been demolished and replaced by two wide, gently sloping flights of steps to each side of the new gate, inspired by the stairs that had framed the gate before the construction of Freedom Square.

The parliament building is made up of two massive blocks in stone that are balanced on slender columns to give the building a sense of lightness, the whole respecting the line of the existing street layout. The northernmost block is principally given over to the parliament chamber, while the south block accommodates members of parliament’s offices and the offices of the Prime Minister and Leader of the Opposition.

Creating a porous urban block was at the forefront of the building’s volumetric design. The two blocks are separated by a central courtyard, which also serves as the main entrance to the building. The courtyard is conceived in such a way that views through to St James’s Cavalier from Republic Street are not obscured.

Generally it is the density and dynamism of a building’s ground floor that brings it to life, driving a hive of activity in the rest of the building; this is how the ground floor was conceived here, as a flexible cultural space, fully fitted out with a full range of multimedia services. It is an ideal space for temporary or permanent exhibitions, all fully visible from outside the building, serving as a sort of cultural outpost at the entrance to Valletta.

Reference

Leave a comment