As the founding publisher of National Lampoon magazine and the person responsible for expanding the Lampoon brand to radio, theater, and film, Matty Simmons led the charge in creating a new kind of comedy during the 1970s. From producing the National Lampoon Radio Hour and stage shows, where he gave work to pre-SNL up-and-comers like John Belushi, Bill Murray, and Gilda Radner to producing Animal House, one of the highest-grossing and most-imitated movies of all-time, Simmons had a vital role in the changing of the guard that occurred in American comedy during the ‘70s. In addition to Animal House, he also produced two other highly-influential films: Vacation and Christmas Vacation. Along with his work with the National Lampoon magazine, stage show, albums, and radio show, these movies have secured Simmons’s place in history as one of the most successful purveyors of comedy ever.

Matty Simmons’s latest book, Fat, Drunk, and Stupid: The Inside Story of the Making of Animal House, comes out today, and it’s a revealing and fun look back at the behind-the-scenes story of the classic college comedy. I recently had the chance to talk to talk Simmons about the making of Animal House, the legacy of the Lampoon, how he turned down an offer from NBC to produce a Saturday night sketch show in the mid-’70s, and why he feels Judd Apatow is in a league of his own when it comes to contemporary comedy.

Have you always had an interest in comedy?

Always … When you grew in Brooklyn, back in those days, you were into Milton Berle and Henny Youngman and people like that. But that was a different kind of comedy, of course. That was mother-in-law jokes. What we did was make popular a new kind of comedy at the Lampoon.

It seems like you ushered in so many comedic talents that went on to work for years and years …

I was just this morning talking about Al Jean and Michael Reiss, who went on [and] for 18 years wrote and produced The Simpsons. Larry David wrote for us. P.J. Rourke, who’s one of the most popular humorists of our time. Henry Beard, who writes a bestseller every year or two. Many other people … Every great comedy show had a Lampoon person involved one way or another the last thirty years. Movie-wise, Ivan Reitman came from the Lampoon, Harold Ramis came from the Lampoon.

John Hughes, also.

John Hughes was an editor at the Lampoon. What happened with John Hughes was, I was having lunch at the Friar’s Club with David Brown, who produced Jaws, and he said, “Oh, we’ve got to do a movie together.” As a gag, I said to him, National Lampoon’s Jaws 3, People Nothing. He looked at me like, “What?” Then, [I] came up with a story I made up on the spot, and he said, “I love it!” and ran to the phone and called his partner, Richard Zanuck. He said, “We’re meeting Ned Tannen,” who was the head of Universal, “tonight at the Rainbow Grill.” He said, “We’ll do this. You’re a producer, we’ll be executive producers.” He calls me back, he says, “Ned wants to do it.”

So, I go back to my office and I call my secretary in, and I had to remember the story I told, you know? I dictated the story, and when they called and told me the studio wanted to do it, I walked into the editorial office, and I know who I was looking for. Two of the editors were sitting there: a guy named Tod Carroll and a guy named John Hughes. Neither of them had ever written a movie script before. I called ‘em into my office, and I said, “This is the story for Jaws 3, People Nothing. You guys are gonna write the screenplay.” And they wrote it. The leading lady was Bo Derek, Richard Dreyfuss was in it, and Joe Dante, who was an unknown director at the time was gonna direct it. The studio had $2 million into pre-production, and [Ned] Tannen called me on the phone: “I have to see you.” He said, “I have to pull the plug.” I was furious. I had just closed Animal House; I was the hottest producer of the year. He wouldn’t tell me why. I found out in later years that [Steven] Spielberg went to the heads of the company and said, “If you do this movie, I’m leaving.” He thought it demeaned him and demeaned Jaws.

And that’s how John Hughes got into the business, and then his first movies were my movies. Vacation, which was a short story he wrote for the Lampoon. “Vacation ’63.”

Was it your idea or his to turn the story into a movie?

Well, it was my idea to make it a movie. He wrote the story, and after I read it, I called him and I said, “We’re making a movie out of this.” When I brought it to Hollywood, the first guy I brought it to was Jeff Katzenberg who was at Paramount. He said it would never make a movie, it was too episodic, too consequential. I said, “Yeah, it’s a road trip. It’s supposed to be episodic. You go from town to town, place to place.” But he didn’t like it, so then my agent brought it to Warner Brothers, and I met with them. Most of them said the same thing, but there was one executive over there — a guy named Mark Canton — who really pulled for it, and it got made.

I didn’t know Larry David wrote for National Lampoon. What was his involvement?

Yeah, [he] only wrote a couple times, but he did a very big feature about his date — it was apocryphal, of course — with Mary Tyler Moore, who was then the biggest star on television. He was this nerdy guy and he pretended he had a date with Mary Tyler Moore, and it was very funny.

A lot of people wrote for the Lampoon, famous writers. And of course, you know about the actors.

Yeah, from the stage show and the Radio Hour.

Lemmings [the National Lampoon stage show] was unknowns. John Belushi, Chevy Chase, Chris Guest, and others. The second show, The National Lampoon Show, [had] John Belushi, Bill Murray, Harold Ramis, Gilda Radner. All unknowns.

It seems like Lorne Michaels kind of gets credit for pulling that group together.

The guy who really pulled it together was a Lampoon editor named Michael O’Donoghue, who was the first head writer for Saturday Night Live. He brought in all those talents from the Lampoon. I had a radio show, which Michael produced before Saturday Night Live, and NBC came to me and said they wanted to do a Saturday night variety show and they wanted to do a National Lampoon show, just like the radio show. I said, “I gotta think about it.” And I thought about it, and I had three kids growing up, I had three magazines, I had stage shows, I had radio. I said, “I can’t handle [it].” I said, “I know what’s gonna happen too. All my writers are gonna go write for television,” which is what happened anyway, because it paid so much more than publishing. And I passed, and that’s how Lorne Michaels got in. He was smart — he grabbed Michael O’Donoghue right off the bat, and Michael brought in Belushi and Gilda and Chevy. All Lampoon people.

What was the casting process like for Animal House?

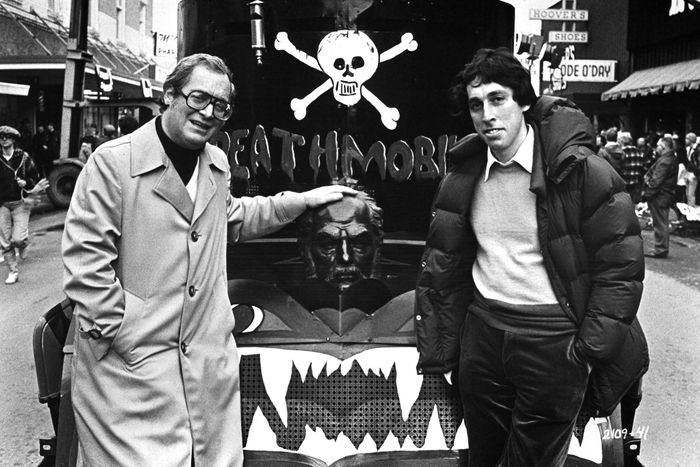

From the moment the treatment was written, Bluto was John Belushi. Remember, we were very, very close. Belushi worked with me for four years. Belushi was in Lemmings, he directed and starred in The National Lampoon Show, and he replaced O’Donoghue as director of the radio show. So, he was automatic. Belushi was definitely gonna be Bluto. Before we had anything, we wrote a rough treatment and that was decided. The others were just people who we cast. The casting was sensational. The casting director, a guy named Michael Cimmins, did a brilliant job. Landis did a great job. Everybody. Reitman and the producers I think did a pretty good job.

You know what it was? [It] was a perfect storm. Everything came together. The actors were just right — perfect. Bill Murray desperately wanted to play Boon, but we didn’t feel right for the role, and Peter Riegert was absolutely perfect for the role. [Harold] Ramis wanted to play Boon too. [He was] one of the writers of the movie, and he was very upset that he didn’t get it, but he got over it ‘cause, as you probably know, he directed Vacation for me, and we’ve remained very close friends ever since.

Besides Jaws 3, People 0, are there any other movies that you tried to get made that didn’t pan out?

Oh, yeah. Are you kidding me? It’s Hollywood. For every one you make, there are five you develop that you don’t make. I did a movie with Judd Apatow that we never made.

What was the Judd Apatow movie?

I think it was called College Bound. I don’t remember exactly. I still … Judd and I talk frequently. He’s never worked for the Lampoon except for that one movie, but he’s a Lampoon freak. I mean, I just spent the day with Billy Bob Thornton, who said he knows everything in the book. He said, “I grew up with the Lampoon. The Lampoon is my Bible.” “You’re my hero,” he says to me, and I think he’s the most talented man in show business. He’s a brilliant guy. Bill Maher said the same thing. I see him often at parties or social events, and he says to me, “I have every copy of the Lampoon except for the first one.”

It seems like it definitely influenced an entire generation.

Yeah, Jim Carrey often says, “We used to light up some weed and listen to Lampoon record albums through the night.” Everybody of that age bracket, guys in their 40s or 50s, grew up on it and loved it. My movies are still huge. I mean, I’m sure you’re aware of it. Animal House is on television all the time. As are the Vacation movies.

Yeah, those are required viewing, even still.

I’ll tell you something that is the most amazing thing in the world. Nobody ever heard anything like this before. Last year, 33 years after the movie released, Animal House made a profit of three million dollars.

Wow. Just off of DVD sales or …

Video and foreign sales. They still play it in theaters out of the country. And merchandise. And cable television. It’s on cable television two, three times a week all over the country and on a lot of local stuff too.

Also, the Belushi “College” poster, I’m sure is still selling like crazy too. Oh, well. That was huge. “Bluto for Senate” or the one of him wearing the college T-shirt. That’s huge too. That T-shirt still sells everywhere, the one that just says, “College” on it.

Yeah. That poster seems like it’s in still in every other dorm room.

Yeah, yeah.

When did you first meet Belushi? What was your first impression of him?

We were casting Lemmings — the first show. The director came to me, and we needed guys who could be funny and act and also play instruments, because the basic element of Lemmings was that it was a parody of Woodstock. He said, “I hear this guy who just started about a month or so ago at Second City is fantastic, and I think he can play instruments.” And I said, “Go to Chicago, call me.” So, he calls me two days later, and he says, “This guy is unbelievable.” I said, “Can he play instruments?” He says, “Well, he plays a little drums, but he told me he could play the guitar, so I went to his house. He played a song for me on his guitar, and I said, ‘Can you play anything else?’ and he played the same song … But he’s unbelievable. He’s the funniest guy.”

So, I checked with some friends in Chicago, and they said the same thing. So, I said to him sign him up and bring him in. And that’s how Belushi got going. He was an instant hit. Raves in the New York Times. All of the reviews, Belushi and [Chevy] Chase got most of the huge reviews. Chase had never acted before. I think he’d been in an underground television show that you could only see in … I don’t know, in a store in Greenwich Village or something.

Throughout the Lampoon stuff and your movies, it seems like you kind of had to keep a lot of the performers in line …

Keep the animals quiet?

[Laughs.] Yeah, exactly. Would you say that’s an accurate assessment?

You know, it’s funny. Michael O’Donoghue wrote me a letter shortly before he died, and he said, “You know, now that I think back on what you went through with us … Now that I write, direct, and produce myself, I can understand what you went through and it must have been hell.” As a matter of fact, it wasn’t hell; it was fun. It was great fun. And I never took them too seriously. I never worried about it.

If you walked into the editorial office at the Lampoon, you’d get high just walking through the door. They were all wacky. Doug Kenney, who was one of the two or three stars of the Lampoon, would disappear for two months at a time. Once, he sent me a postcard saying, “Next time, get a Yalelie.” You know, ‘cause I got him from Harvard. One time, he took one of the production managers, a good-looking young girl. He left with her and pitched a tent on the beach in Martha’s Vineyard and stayed there for a month and a half. They’re all a little nutty, but you’ve got to be a little nutty to write that kind of dark, crazy humor.

[John] Hughes, as a matter of fact, was the most down-to-earth. I think that’s reflected in his movies. Hughes mostly wrote about his own life experiences. Like Vacation … He went on that road trip with his parents when he was a kid. He writes about his high school experiences. But he was a brilliant, brilliant … I believe that John Hughes was the most successful — from the point of view of box office — comedy writer in the history of film. He did 101 Dalmatians, Home Alone … the guy was worth hundreds of millions of dollars.

How do you feel like comedy has changed over the past few decades?

I’m annoyed by a lot of it because I had a rule at the Lampoon: You can say anything you want, but it’s got to be redeemably funny. Now, to me, most comedy just says anything they want without being redeemably funny. They think that if you say “shit” or “fuck you,” that’s funny. It’s funny if it’s in the right context — if it’s a funny line or a funny situation. But just saying the obscenities isn’t funny. And too many movies now … and TV, they don’t go that far, but … Most TV now depends on just saying or doing crazy things even if they’re not funny and getting big laughs from it.

That’s one reason [Judd] Apatow is so successful is what he does is usually redeemably funny. He goes far, but it’s funny.

Besides Apatow’s stuff, are there any other modern comedies that you feel are doing things right?

Apatow is all by himself as far as contemporary comedy. Todd Phillips has made some good movies, but Apatow has consistently produced the funniest movies in the last 10 to 12 years. From Animal House through 1990, I think the combination of John Hughes and my stuff, the Lampoon stuff, was the funniest … and Ramis has done some very funny things. Reitman has done a few too.

Did you feel like when Animal House was being made, it was kind of a rare thing to have that group together — Harold Ramis, Ivan Reitman, John Landis, Belushi?

You know, none of us had ever done a movie before. Reitman had done a couple triple Z $80,000-budget movies in Canada, but he knew nothing about how to make a movie in Hollywood. None of the writers and I had made a movie before. We’d done theater — at least I had and Ramis had, but [co-writers] Kenney and [Chris] Miller had never done anything like that. We just flew by the seat of our pants. We just did what we thought was right. Once again, the studio hated it. I brought it to Warners first; the head of the studio said it would never make a movie. I brought it to Universal and the head of the studio hated it, and two junior executives at Universal talked to him and begged him and pleaded with him. Finally, since the budget was only $2.8 million and the Lampoon was so red hot, he said, “I’m doing this ‘cause it’s the National Lampoon” and greenlighted the movie. And to date, all in with everything — TV, video, box office — 600 million dollars. And remember that when it opened, tickets were three dollars.

Are there any specifics in the movie that are your contributions that you could point out?

I don’t like to discuss … Any movie I work on, I work with the writers first of all, and then of course, heavily on the casting. I never like to discuss what I wrote or what kind of contributions I made, because the writers get the credit for the movie, and they deserve it, and that’s it. My job, I get credit for producing it. I consider working with the writers and casting as part of what I do. So, I did write some stuff for it, but I don’t want to discuss it because I don’t want to take credit away. They did a brilliant job.

If anything, I did more taking out than putting in. I continually got rid of scatological humor, which I don’t think is funny on [film]. Bridesmaids … was a very, very funny movie, except for the, to me, the shitting scene lost me. I don’t think it was necessary, I don’t think it was funny, but the rest of the movie was really funny and it did really well … I don’t think they needed it.

What I did was suggest things. For example, you see the guys lined up in front of Dean Wormer, and he’s telling them they’re gonna get thrown out of school, and Flounder’s dead-drunk from the night before … They wanted and Landis wanted him [to] throw up on the Dean, and I said, “No way. I’m not gonna sit in the theater and watch him throwing up.” What I came up with was cut to the secretary outside the office, and you hear him throw up, and that’s twice as funny. They agreed. The audiences loved it. Use your imagination to tell you. You can see it in your mind. That’s what I think those people with Bridesmaids should have done.

Matty Simmons’s new book, Fat, Drunk, and Stupid: The Inside Story Behind the Making of Animal House hits the shelves today, and is available in hardcover and e-book form.

Bradford Evans is a writer living in Los Angeles.