What to Do About William Faulkner

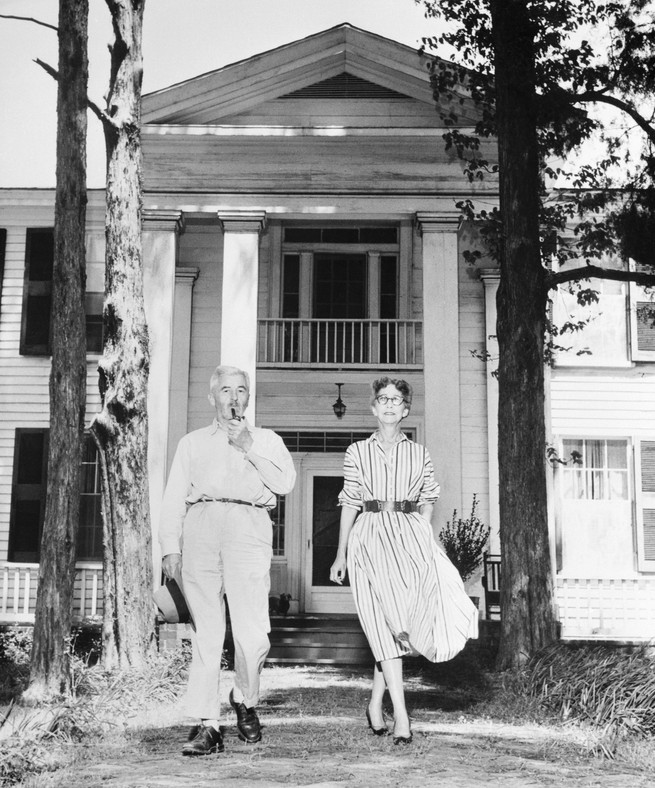

A white man of the Jim Crow South, he couldn’t escape the burden of race, yet derived creative force from it.

In June 2005, Oprah Winfrey announced a surprising choice as the 55th selection for her influential book club. The coming months would be, she proclaimed, a “Summer of Faulkner,” focused on three of his novels—As I Lay Dying, The Sound and the Fury, and Light in August, available in a special 1,100-page box set weighing in at two pounds. Oprah’s website posted short videotaped lectures by three literature professors to assist readers in making sense of the writer’s notoriously demanding prose. The Faulkner trilogy quickly rose to the No. 2 spot on Amazon’s best-seller list. Some literary critics hailed Winfrey for bringing William Faulkner back into popular consciousness; others challenged any notion of recovery or revival, asking whether he had ever really gone away.

In the decade and a half since then, the issues of race and history so central to Faulkner’s work have grown only more urgent. How should we now regard this pathbreaking, Nobel Prize–winning author, who grappled with our nation’s racial tragedy in ways that at once illuminate and disturb—that reflect both startling human truths and the limitations of a white southerner born in 1897 into the stifling air of Mississippi’s closed and segregated society? In our current moment of racial reckoning, Faulkner is certainly ripe for rigorous scrutiny.

Michael Gorra, an English professor at Smith, believes Faulkner to be the most important novelist of the 20th century. In his rich, complex, and eloquent new book, The Saddest Words: William Faulkner’s Civil War, he makes the case for how and why to read Faulkner in the 21st by revisiting his fiction through the lens of the Civil War, “the central quarrel of our nation’s history.” Rarely an overt subject, one “not dramatized so much as invoked,” the Civil War is both “everywhere” and “nowhere” in Faulkner’s work. He cannot escape the war, its aftermath, or its meaning, and neither, Gorra insists, can we. As the formerly enslaved Ringo remarks in The Unvanquished (1938) during Reconstruction-era conflict over voting rights, “This war aint over. Hit just started good.” This is why for us, as for Jason and Quentin Compson in The Sound and the Fury (1929), was and again are “the saddest words.” As Gorra explains, “What was is never over.”

In setting out to explore what Faulkner can tell us about the Civil War and what the war can tell us about Faulkner, Gorra engages as both historian and literary critic. But he also writes, he confesses, as an “act of citizenship.” His book represents his own meditation on the meaning of the “forever war” of race, not just in American history and literature, but in our fraught time. What we think today about the Civil War, he believes, “serves above all to tell us what we think about ourselves, about the nature of our polity and the shape of our history.”

The core of Gorra’s book is a Civil War narrative, which he has created by untangling the war’s appearances throughout Faulkner’s fiction and rearranging them “into something like linearity.” From the layers and circularities and recurrences and reversals of Faulkner’s 19 novels and more than 100 short stories, Gorra has constructed a chronological telling of Yoknapatawpha’s war, of the incidents and characters who appear in the writer’s extended chronicle of his invented “postage stamp” world. Faulkner took liberties with the historical order of events; what he sought to depict was the “psychological truth of the Confederate home front” and the war’s aftermath. This is work, Gorra argues, that actual documents of the period would be hard-pressed to do. And that psychological truth certainly could not have been derived from study of the racist historiography of Faulkner’s era, which he insisted he never even read. Instead, this understanding is the product of what Toni Morrison once called Faulkner’s “refusal-to-look-away approach” to the burden of his region’s cruel past.

Faulkner enacts this refusal through his practice of looking again, of revisiting the same characters and stories, and through the prequels and sequels and outgrowths of those he has already told, digging deeply into the hidden and often shocking truths of the South he portrays. Gorra endeavors to unknot and clarify Faulkner’s oeuvre by reconstructing it himself, but his act of literary explication is also one of participation—a joining in the Faulknerian process. Gorra renarrates these Civil War stories as he seeks to come to terms both with America’s painful racial legacies and with William Faulkner.

Perhaps the most powerful of Faulkner’s tellings of the Civil War story is Absalom, Absalom! (1936), a novel structured around Quentin Compson’s own refusal to look away. Although Faulkner insisted that Quentin did not speak for him, Gorra has “never quite believed him.” Quentin’s search to understand why Charles Bon was murdered during the very last days of the war unfolds through his elaboration of successive narratives in a manner not unlike Faulkner’s own. Unsatisfied with each version of the story he uncovers, Quentin looks again, arriving through ever more disturbing revelations at the South’s original sin: the distorting and dehumanizing power of race. It is race that pulls the trigger. “So it’s the miscegenation, not the incest, which you cant bear,” Bon says just before Henry, at once his brother and his fiancée’s brother, shoots him.

To think of this novel appearing in the same year as Gone With the Wind is startling. It was moonlight and magnolias, rather than a searing portrait of the persisting legacies of slavery, that captured the public’s acclaim: Margaret Mitchell, not Faulkner, won the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction in 1937. But Faulkner’s period of “explosive productivity,” beginning in 1929—13 books in 13 years—attracted a different sort of attention, because of his formal innovations and literary experimentalism, not just his unvarnished portrayals of race. In a 1939 essay, Jean-Paul Sartre compared him to Proust, and Faulkner became an idol in the eyes of young French intellectuals as well as literary critics around the world. Faulkner might not have won the Pulitzer, but he was on the path to his 1949 Nobel.

Gorra notes the “ever-increasing importance of race” in Faulkner’s fiction. Yet society’s racial attitudes and practices were evolving even more rapidly than Faulkner’s own. As the civil-rights movement gained momentum after the end of World War II, Faulkner engaged in more explicit public commentary about America’s divisions and inequities. Like critics in those years and ever since, Gorra struggles to come to terms with the distressing views Faulkner frequently articulated on questions of racial progress and racial justice. Gorra does not look away from Faulkner’s troubling public statements or from some disconcerting stereotypes and assumptions in his literary work that became newly jarring as social attitudes shifted.

A great deal is at stake in Gorra’s effort. We are in a time when authors’ reputations are overturned, their works removed from reading lists, their achievements devalued because of their blindness on questions we now see with different eyes. At the outset of his book, Gorra reminds us of persisting debates over Joseph Conrad, initially stimulated by a 1977 Chinua Achebe essay labeling him an apologist for imperialism. Today, Gorra believes, Faulkner “stands to us as Conrad does,” in need of reexamination and an updated understanding that confronts his racist shortcomings.

Faulkner, Gorra concedes, “remained a white man of the Jim Crow South and did not always rise above it. At times his words both can and should make us uncomfortable.” His fiction offers an “all-too forgiving depiction of slaveholder paternalism.” His novels and stories fail to render slavery’s physical cruelties; they include no depiction of an auction, a family separated by sale, or a whipping. Many of his Black characters seem incomplete, although they’re certainly not the caricatured stereotypes typical of so much white southern writing of his time. Faulkner remarked upon white men who had “the courage and endurance to resist … Reconstruction.” The Unvanquished presents John Sartoris as a leader of the local Klan admirably determined to keep “the carpetbaggers from organizing the negroes into an insurrection,” which was Sartoris’s view of the Black claim on the franchise. As Gorra observes, Faulkner’s “picture of black voters as inevitably ignorant and corruptible simply parrots the view of Reconstruction that was current in Faulkner’s childhood and for some decades thereafter.” A 1943 short story Faulkner wrote for The Saturday Evening Post presents the slave broker and Confederate general Nathan Bedford Forrest in a generous manner that Gorra finds particularly “hard to stomach.” At the same time, Gorra points out, the depiction of enslaved people fleeing to freedom and securing their own emancipation transcends the historiography of Faulkner’s time and anticipates that of our own. He is no apologist for the Old South, and resists in any way glorifying the war, unlike almost every other white southerner of his era.

The public pronouncements Faulkner made on race as the civil-rights movement unfolded are in many ways even more disturbing than the shortcomings Gorra identifies in his fiction. In an appalling drunken interview with the British Sunday Times in 1956, Faulkner invoked the specter of race war if the South were compelled to integrate, but when his words were widely reviled, he denied ever having uttered them. He regularly spoke out against lynching and deplored the 1955 murder of Emmett Till, saying that any society that murdered children didn’t “deserve to survive, and probably won’t.” But he had once suggested that mobs, “like our juries … have a way of being right.” Gorra underscores the “incoherence” of Faulkner’s position as both critic and defender of the white South’s resistance to change.

In many ways, he was a quintessential white southern “moderate,” an identity much scrutinized as the civil-rights movement gathered momentum. He condemned violence and recognized the need to end segregation, but he rejected what Martin Luther King Jr. later described as “the fierce urgency of now.” Indeed, it was the moral failures of just such moderates that King would directly assail in his 1963 “Letter From Birmingham Jail.” Faulkner urged patience and delay and spoke out against federal coercion of the white South. His critics thought he should have known better. As James Baldwin explained in a 1956 essay condemning his views on desegregation, Faulkner hoped to give southern whites the time and opportunity to save themselves, to reclaim their moral identity. But their salvation could come, if at all, only at the cost of postponing justice for Black Americans, which Baldwin made clear was no longer conceivable.

Gorra assembles quite a bill of failings, especially if we view Faulkner with the assumptions of our time and place rather than his own. Yet having meticulously acknowledged all of this, Gorra makes his claim for Faulkner the writer by reproving Faulkner the man. “When writing fiction,” Faulkner “became better than he was.” He had, Gorra argues, an uncanny ability to “think his way within other people,” to inhabit their being so as to erase preconceptions and prejudices in the very act of portraying their minds and souls. Through fiction, Faulkner could “stand outside his Oxford, his Jefferson, and see the behavior his people take for granted, the things they don’t even question.” As Gorra presents it, the act of writing bestowed an almost mystical clear-sightedness. Yet that clarity was always challenged in the fetid Mississippi air that Faulkner, like all his characters, had to breathe. And it is that very tension, the combination of the flaws and the brilliance, that for Gorra makes his case.

Is this rendering of Faulkner’s weaknesses as the source of his strength just an act of interpretive jiu‑jitsu? Or perhaps a reversion to a romantic notion of redemptive genius? Or is Gorra influenced by what Faulkner himself urged upon posterity: that his life be “abolished and voided from history,” leaving only “the printed books”? After all, Faulkner once declared that he wanted his epitaph to read “He made the books and he died.”

But Gorra insists on the importance of the teller and the tale, as well as on the creative force Faulkner derived from the burden of race, which he could not escape. It is because of, not in spite of, Faulkner’s shortcomings that we must continue to engage with his work: These failures are product and emblem of the legacies of racial injustice that shape us all. In his Nobel Prize speech in 1950, Faulkner declared that the only thing worth writing about was “the human heart in conflict with itself.” He lived that conflict even as he wrote about it. His struggles forced him to experiment and to innovate, yielding both his aesthetic and his ethical insight. These very difficulties—“the drama and … power of his attempt to work through our history, to wrestle or rescue it into meaning”—are what make Faulkner so worthwhile. We read him because he takes us with him into our national heart of darkness, into the shameful history we have still failed to confront or understand. Our past, Gorra and Faulkner agree, is “never over.” Or certainly not yet.

When you buy a book using a link on this page, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.