The Solitude of William Faulkner

For nearly half a century, Malcolm Cowley has adorned the American literary scene as critic, poel, and literary historian. William Faulkner was being little read by his own countrymen in the early 1940s when the two initiated a correspondence that was to produce THE PORTABLE FAULKNERand to provide Faulkner's own illumination of his finest works. The account of that relationship is drawn from THE FAULKNER-COWLEY FILE,to be published next month by Viking.

by MALCOLM COWLEY

A, ALMOST every critic dreams of discovering a great work that has been neglected by other critics. Someday might he come upon an author whose reputation is less than his achievement and in fact is scandalously out of proportion with it, so that other voices will be added to the critic’s voice, in a swelling chorus, as soon as he has made his discovery? That is the dream.

At least once in my critical career I had the good luck to find it realized.

But let me explain that I was by no means the first to discover William Faulkner. The man who most deserves that credit is a lawyer in Oxford, Mississippi, an older friend, Phil Stone, who knew him almost from boyhood, who gave him books to read, and who praised his early poems and stories. Later there were many others both here and abroad. There was in fact a small chorus of admirers, which was chiefly composed of creative writers. But after 1936 — the year of Absalom, Absalom!, a difficult book to understand — it was drowned out by a larger chorus of academic critics, almost all contemptuous at the time, and by a deafening frog-pond croak of daily and weekly reviewers. The public, which had been briefly excited by Sanctuary in 1931, had ceased to read his work.

Consider what might be called Faulkner’s quoted value on the literary stock exchange. By the middle years of World War II he had published two books of poems, eleven novels — each an extraordinary work in its own fashion — two collections of stories, and two cycles of stories, The Unvanquished and Go Down, Moses, representatives of a hybrid form between the random collection and the unified novel; there were seventeen books in all. In eleven of the books, he had created a mythical county in northern Mississippi and had told its story from Indian days to what he regarded as the morally disastrous present; it was a sustained work of the imagination such as no other American writer had attempted. Apparently, no one knew that Faulkner had attempted it. His seventeen books were effectively out of print and seemed likely to remain in that condition, since there was no public demand for them. As for his value on the literary stock exchange, in 1944 his name wasn’t even listed there.

It was scarcely listed in the immense catalogue of the New York Public Library, where, at the time, there were cards for only two of his books, A Green Bough and The Hamlet. The other fifteen were hard to find in the secondhand bookstores on Fourth Avenue. But luckily I owned many of the books, since I had reviewed them in the New Republic as they appeared. Gradually and with errors in judgment, I was beginning to perceive a pattern that lay behind them.

I had some leisure in the early months of 1944, owing to a generous grant from the late Mrs. Mary Mellon. I determined to write a long essay on Faulkner and to see whether it might help to redress the balance between his worth and his reputation. But first I sent a letter to the author, addressing him in Oxford. Mississippi; I said that I wanted to meet him and ask questions about his life and his aims. Three months went by before I received an answer, in an envelope that bore the address of the Warner Brothers studio in Burbank, California.

Hollywood, Sunday, 7 May. [1944]

Dear Mr. Cowley:

I just found your letter of last Feb. by idle chance today. Please excuse this. During the last several years my correspondence has assumed a tone a divination of which your letter implies. My mail consists of two sorts: from people who dont write, asking me for something, usually money, which being a serious writer trying to be an artist, I naturally dont have; and from people who do write telling me I cant. So, since I have already agreed to answer No to the first and All right to the second, I open the envelopes to get the return postage stamps (if any) and dump the letters into a desk drawer, to be read when (usually twice a year) the drawer overflows.

I would like very much to have the piece done. I think (at 46) that I have worked too hard at my (elected or doomed, I dont know which) trade, with pride but I believe not vanity, with plenty of ego but with humility too (being a poet, of course I give no fart for glory) to leave no better mark on this our pointless chronicle than I seem to be about to leave.

As you can see from above, I am at the salt mines again. It would cost more to come here than to come to Miss. This town is crowded with war factory workers and troops, is unpleasant. But I have a cubbyhole which you are welcome to share until June 1, when my family is coming out. In the fall I will go back home. I dont know when I will come East, I mean to New York. I would like to, but I never seem to have that much money anymore, as I try to save what l earn here to stay at home as long as possible on.

I would like the piece, except the biography part. You are welcome to it privately, of course. But I think that if what one has thought and hoped and endeavored and failed at is not enough, if it must be explained and excused by what he has experienced, done or suffered, while he was not being an artist, then he and the one making the evaluation have both failed.

Thank you for your letter, and again excuse the time lapse.

By the time Faulkner’s letter arrived, I was editing a Portable Hemingway for the Viking Press. I was late with my copy, the presses were waiting, the Vikings were sending telegrams, and I hallexpected to find a shipload of berserk warriors moored in front of my door. It wasn’t until the job was finished and the threat of sanctions lifted that I wrote Faulkner again.

RFD Gaylordsvillc, Conn.

July 22, 1944.

Dear Faulkner:

You can see that I’m pretty nearly as bad as you are about answering letters, and I haven’t the excuse of a system either; it’s just a mixture of indolence and busyness, one part of each, and life as a succession of deadlines that I just fail to meet.

I want very much to write the article about you, and I want to meet you too, but it’s quite possible to write the article without meeting you and without knowing very much about your biography, which wouldn’t go into the article anyway you’re right about that point; but I ought to know something about it for the thinking that has to be done before the article is written, so that I wouldn’t make too many bad guesses. Fd like to put in about a month or six weeks of work on it, and that’s why I’m trying to sell it in advance to some magazine that would pay me for my time: and later I could use it in a book I’d planning to do.

Status of the magazine negotiations: I tried the Atlantic while I was in Boston, and the net result was a luncheon at the St. Botolph Club, lobster, sherry, old fashioneds, two bottles of Bordeaux and some very old rum. The Atlantic turned thumbs down (thumbs a little greasy with lobster dipped in butter) . . . now I’m working on Harper’s. . . .

Do you want to hear a New York market report on your standing as a literary figure?

It’s about what I suggested in my other letter — very funny, and a great credit to you, but bad for your pocketbook. First, in publishing circles your name is mud. They are all convinced that your books won’t ever sell, and it s a pity isn’t it? they say, with a sort of pleased look on their faces. . . . Now, when you talk to writers instead of publishers or publishers’ pet critics about the oeuvre of William Faulkner, it’s quite a different story; there you hear almost nothing but admiration, and the better the writer the greater the admiration is likely to be. Conrad Aiken, for example, puts you at the top of the heap. . . . The funny thing is the academic and near-academic critics and the way they misunderstand and misstate your work. . . .

So, a good piece on your work has to be written, and if my indolence doesn’t get the best of me, I’ll try hard to write it — and thank God, I’m too indolent to stop working once I get started.

Now, there’s one question I wish to God you’d answer for me, not because I want to quote you, but so that I won’t make a fool of myself when I come to write the piece. It’s about the symbolism in your work. It’s there, all right, and I don’t see how anybody but a learned critic can miss it — I mean, of course, that Sutpen’s Hundred, in “Absalom, Absalom!,” becomes, for the reader at least, a symbol of the old South, with the manner of its building and its decay after the war, and its owner killed by a poor white, and the only survivor of the Sutpen family a mulatto; that’s almost an allegory or legend, and you repeat the legend explicitly in the fourth part of “The Bear.”

Once in the Southern Review, Cleanth Brooks, I think it was,1 gave a whole allegorical scheme for “Sanctuary,” saying that the gal was the South, raped by modern industry (in the form of Popeye), except that modern industrial civilization is so sterile it didn’t have strength to rape her and had to get a substitute. I thought that Brooks’s scheme was a lot too definhe and pat, but still Popeye does seem to have something of the quality you impute to the representatives of modern civilization, and the sterility pops up again in the reporter in “Pylon” — and that same book has the sex in the airplane, a marvelous scene with no double entendre but with a double meaning, certainly. Well, the question is (speaking roughly) how much of the symbolism was intentional, deliberate? Or is that the sort of question I shouldn’t ask, even for my own information? . . .

It was a matter of three or four months before Faulkner answered my query. In the meantime I had been rereading his books, I had assembled a mass of notes on them, and I had started work on an essay that promises to become too long for magazine publication. Then I had done two other things that would have some bearing on his next letter. I had first sawed off a steak or rib roast from the carcass of my essay and had persuaded the New York Times Book Review to publish it. Second, I had written Faulkner repeating my question about his symbolism.

Oxford. Saturday.

[Early November, 1944]

Dear Maitre:

I saw the piece in the Times Book Rreview]. It was all right. If that is a fair sample, I dont think I need to see the rest of it before publication because I might want to collaborate and you’re doing all right. But if you want comments from me before you release it, that’s another horse. So I’ll leave it to you whether I see it beforehand or not.

Vide the paragraph you quoted: As regards any specific book, I’m trying primarily to tell a story, in the most effective way I can think of, the most moving, the most exhaustive. But I think even that is incidental to what I am trying to do, taking my output (the course of it) as a whole. I am telling the same story over and over, which is myself and the world. Tom Wolfe was trying to say everything, the world plus “I” or filtered through “I” or the effort of “I“ to embrace the world in which he was born and walked a little while and then lay down again, into one volume. I am trying to go a step further. This I think accounts for what people call the obscurity, the involved formless “style”, endless sentences. I’m trying to say it all in one sentence, between one Cap and one period. I’m still trying to put it all, if possible, on one pinhead. I don’t know how to do it. All I know to do is to keep on trying in a new way. I’m inclined to think that my material, the South, is not very important to me. I just happen to know it, and dont have time in one life to learn another one and write at the same time. Though the one I know is probably as good as another, life is a phenomenon but not a novelty, the same frantic steeplechase toward nothing everywhere and man stinks the same stink no matter where in time. . . .

I think Quentin, not Faulkner, is the correct yardstick here. I was writing the story [Absalom, Absalom!], but he not I was brooding over a situation. I mean, I was creating him as a character, as well as Sutpen et al. He [Quentin] grieved and regretted the passing of an order the dispossessor of which he was not tough enough to withstand. But more he grieved the fact (because he hated and feared the portentous symptom) that a man like Sutpen, who to Quentin was trash, originless, could not only have dreamed so high but have had the force and strength to have failed so grandly. Quentin probably contemplated Sutpen as the hypersensitive, already self-crucified cadet of an old long-time Republican Philistine house contemplated the ruin of Sampson’s portico. . . . He grieved and was moved by it but he was still saying “I told you so” even while he hated himself for saying it. You are correct; I was first of all (I still think) telling what I thought was a good story, and I believed Quentin could do it better than I in this case But I accept gratefully all your implications, even though I didn’t carry them consciously and simultaneously in the writing of it. In principle I’d like to think I could have. But I don’t believe it would have been necessary to carry them or even to have known their analogous derivation, to have had them in the story. Art is simpler than people think because there is so little to write about. All the moving things are eternal in man’s history and have been written before, and if a man writes hard enough, sincerely enough, humbly enough, and with the unalterable determination never never never to be quite satisfied with it, he will repeat them, because art like poverty takes care of its own, shares its bread. . . .

Faulkner had given me two hints about his work that I confess to not having developed in the essay I was writing. The first was that what he regarded as his essential subject was not the South or its legend, but rather the human situation, “the same frantic steeplechase toward nothing everywhere.” He approached it in terms of Southern material because, as he said, “I just happen to know it, and dont have time in one life to learn another one and write at the same time.” But he hoped that the material would have more than a regional meaning, and very often — as in his comparison of Sutpen with Sampson — he thought back to archetypes, not in Southern legend, but in the Bible.

The second hint was that he tried to present characters rather than ideas. In that respect his work reminds me of what Northrop Frye says about Shakespeare’s plays: that there is not a passage in them “which cannot be explained entirely in terms of its dramatic function and context . . . nothing which owes its existence to Shakespeare’s desire to ‘say’ something.” Faulkner was telling me that he had aimed at a sort of dramatic impersonality not only in Absalom, Absalom! but in all his novels.

I felt in November, 1944, that an attempt to discuss the complicated relation between author and characters would carry me far beyond the introductory essay on which I was working. At the time, I was more concerned with my question about Faulkner’s symbolism, and here I was delighted with his answer. It seemed to me then it still seems to me — that the deliberate use of symbols is a dangerous literary device, since the author may let himself be distracted from the primary reality of his characters and situations in his effort to give them secondary or symbolic meanings. I felt that truly effective symbols, like those in Faulkner’s novels, were produced almost unconsciously, when the author was so deeply absorbed in his story that he made it larger than life. Faulkner’s letter helped to confirm me in this belief, and I went back to work on the essay with renewed enthusiasm.

AT THIS point there is a gap of several months in the correspondence. What hadn’t been mentioned in my letters is that I had been urging the Viking Press to publish a Portable Faulkner as a sequel to the Portable Hemingway that I had finished in July. The proposal elicited some interest, but no enthusiasm. I was told that Faulkner’s audience was too limited and that his critical standing was too dubious to justify such a book; it would have no sale. While arguing the point, I had completed my essay, and I was eager to see it in type. But where? The essay had lengthened to the point where no magazine of general circulation would be willing, at the time, to print the whole of it. Accepting the fact, I did the best I could. I beefed it.

The term is one that I first heard from George Milburn, the author of Catalogue, an entertaining first novel about an Oklahoma town. His friends waited for a second novel, but it didn’t appear. When I asked him about it, he looked unhappy.

“I was spending the winter on Cape Cod,” he said, “and I had the book pretty near finished. Then I wanted a pair of riding boots, so I cut off a chunk of it and sold it to the New Yorker. There was a bill I owed at the store, and I cut off another chunk. Whenever I needed cash I sold a piece of that novel. It was like I had a steer hanging in the woodshed and was always cutting off steaks. By the end of the winter, Jesus, I’d beefed the whole novel.”

So I beefed the essay and published it in sections, wherever an editor was hungry for words. First, there had been the article for the New York Times Book Review. There I sawed out a longer section and sent it to Hat smith, the publisher of the Saturday Review. There was a still longer section remaining, on Faulkner’s legend of the South, and I sent it to Allen Tate, who was editing the Sewanee Review. Allen printed it in his summer number. Then suddenly I had a call from Marshall Best, who asked me to see him at the Viking office.

“It seems to us,” he said, “that Faulkner is attracting a great deal of attention in the magazines.”

I modestly agreed.

“Under the circumstances,” he went on, “we feel that a Portable Faulkner might have a chance to find readers. How soon could you have the copy ready?”

A few days later I wrote a jubilant letter to Faulkner, who was then serving another sentence in Hollywood.

August 9, 1945.

Dear Faulkner:

It’s gone through, there will be a Viking Portable Faulkner, and it seems a very good piece of news to me. . . .

And now comes the big question, what to include in the book. It will be 600 pages, or a shade more than 200,000 words. The introduction won’t be hard; it will be based on what I have written already (bearing your comments in mind); but what about the text?

I have an idea for that, and I don’t know what you’ll think about it. Instead of trying to collect the “best of Faulkner” in 600 pages, I thought of selecting the short and long stories, and passages from novels that are really separate stories, that form part of your Mississippi scries — so that the reader will have a picture of Yocknapatawpha County [I misspelled the name in those days] from Indian times down to World War II. . . .

Thursday [August 16, 1945]

Dear Cowley:

The idea is very fine. I wish we could meet, but that seems impossible now. I will do anything I can from here.

By all means let us make a Golden Book of my apocryphal county. I have thought of spending my old age doing something of that nature: an alphabetical, rambling genealogy of the people, father to son to son.

I would hate to have to choose between Red Leaves and A Justice, also another one called Lo! from Story Mag. several years ago. . . .

What about taking the whole 3rd section of SOUND AND FURY? That Jason is the new South too. I mean, he is the one Compson and Sartoris who met Snopes on his own ground and in a fashion held his own. Jason would have chopped up a Georgian Manse and sold it off in shotgun bungalows as quick as any man. But then, this is not enough to waste that much space on, is it? The next best would be the last section, for the sake of the negroes, that woman Dilsey who “does the best I kin.”

AS I LAY DYING is simple tour de force, though I like it. But in this case it says little that spotted horses and Wash and Old Man would not tell.

THE HAMLET was incepted as a novel. When I began it, it produced Spotted Horses, went no further. About two years later suddenly I had The HOUND, then JAMSHYD’S COURTYARD, mainly because SPOTTED HORSES had created a character I fell in love with: the itinerant sewing-machine agent named Suratt. Later a man of that name turned up at home, so I changed my man to Ratliff for the reason that my whole town spent much of its time trying to decide just what living man I was writing about, the one literary criticism of the town being “How in the hell did he remember all that, and when did that happen anyway?”

Meanwhile my book had created Snopcs and his clan, who produced stories in their saga which are to fall in a later volume: MULE IN THE YARD, BRASS, etc. This over about ten years, until one day I decided I had better start on the first volume or I’d never get any of it down. So I wrote an induction toward the spotted horse story, which included BARN BURNING and WASH, which I discovered had no place in that book at all. Spotted horses became a longer story, picked up the HOUND, rewritten and much longer and with the character’s name changed from Cotton to Snopes, and went on with JAMSHYD’S COURTYARD. . . .

Wish to hell we could spend three days together with these books. Write me any way I can help.

“Suppose you use the last section, the Dilsey one, of SOUND & FURY,” Faulkner said in another letter from Hollywood, “and suppose (if there’s time: I am leaving here Monday for Mississippi) I wrote a page or two of synopsis to preface it, a condensation of the first 3 sections, which simply told why and when (and who she was) and how a 17 year old girl robbed a bureau drawer of hoarded money and climbed down a drain pipe and ran off with a carnival pitchman.” The suggestion aroused my enthusiasm. On October 1, I made a progress report to Marshall Best of the Viking Press.

Dear Marshall:

After a lot of rereading and excogitation, I have drawn up a tentative table of contents for the Faulkner book. It runs to 248,000 words, but I can squeeze 15,000 words out of it on demand (“Wedding in the Rain” and “A Rose for Emily”). It contains no complete novel — though it does contain one complete story of 47,000 words and another of 36,000 words. What it offers is a suggestion of Faulkner’s epic, the story of a Mississippi county and its people from the days when it was inhabited by Chickasaws down to the Second World War, as well as the long stories in which Faulkner is a master. I think that for the first time, people will be able to see his talent as a whole. . . .

About printer’s copy, I still lack tear-up copies of “Dr. Martino,” “The Sound and the Fury” and “Sanctuary.” I can get along without them, in a pinch, by sacrificing my own copies, but it would help me a lot to have them. . . .

In those days the problem of assembling a printer’s manuscript was sometimes a difficult one for anthologists. It was before the time of inexpensive photocopies. Linotypers objected to working from a bound book — they still object — and there was an extra charge if they had to set type from both sides of a printed leaf. Accordingly, the anthologist was urged to tear apart two copies of any book from which he was making long extracts. In the case of Faulkner’s books, however, even one tear-up copy was hard to find. Viking advertised in the trade journals and obtained a few of them, but nobody came forward with others. In the end, feeling like Alaric at the sack of Rome, I had to sacrifice some of my first editions.

Meanwhile I had written Faulkner a letter, now lost, in which I suggested that he might collect his short stories in a volume arranged by cycles: the Indian cycle, the Compson cycle, the town cycle, the Ratliff-Bundren cycle, and all the others. I also told some anecdotes about his reputation in Europe. Again he answered promptly.

[Oxford]

Friday. [October 5, 1945]

Dear Cowley:

Yours at hand this morning, I am getting at the synopsis right away, and I will send it along.

The idea about the other volume [the collected stories] is pretty fine. There are some unpublished things which will fit it that I had forgot about, one is another Indian story which Harold Ober has, the agent I mean. It is the story of how Boon Hogganbeek, in THE BEAR, his grandfather, how he won his Chickasaw bride from an Indian suitor by various trials of skill and endurance, one of which was an eating contest. I forget the title of it. There is also another Sartoris tale, printed in STORY two years ago, about Granny Millard and General Forrest, told by the same Bayard who told THE UNVANQUISHED. There is an unpublished Gavin Stevens story which Ober has, about a man who planned to commit a murder by means of an untameable stallion. You may have seen these. If you have not, when you are ready to see them, I will write Ober a note.

Yes, I had become aware of Faulkner’s European reputation. The night before I left Hollywood I went (under pressure) to a party. I was sitting on a sofa with a drink, suddenly realised I was being pretty intently listened to by three men whom I then realised were squatting on their heels and knees in a kind of circle in front of me. They were Isherwood, the English poet and a French surrealist, Hélion: the other one’s name I forget. I’ll have to admit though that I felt more like a decrepit gaffer telling stories than like an old master producing jewels for three junior co-laborers.

I’ll send the synopsis along. It must be right, not just a list of facts. It should be an induction I think, not a mere directive.

THE induction to the Dilsey section of The Sound and the Fury arrived two weeks later in a fat envelope. It was something vastly different from the “page or two of synopsis” that Faulkner had projected in a letter from Hollywood. Instead, it was a manuscript of twenty or thirty pages, a genealogy, rich in newly imagined episodes, of the Compson family over a period of almost exactly two centuries, beginning with the battle of Culloden in 1745.

Enclosed with the genealogy was a letter written in the tone of exultation mingled with apology that I have known other writers to adopt after completing a work they felt would stand for a long time. And why the apology? Ostensibly it was offered to me, for the length of the manuscript, but I suspect it was really offered to the fates that had been kind beyond reason but that still expected him to be humble and submissive, else they would strike him down in his pride.

[Oxford]

Thursday. [October 18, 1945]

Cher Maitre:

Here it is. I should have done this when I wrote the book. Then the whole thing would have fallen into pattern like a jigsaw puzzle when the magician’s wand touched it.

NOTE: I dont have a copy of TSAF, so if you find discrepancies in chronology (various ages o people, etc.) or in the sum of money Quentin stole from her uncle Jason, discrepancies which are too glaring to leave in and which you dont want to correct yourself, send it back to me with a note. As I recall, no definite sum is ever mentioned in the book, and if the book says TP is 12, not 14, you can change that in this appendix.

I think this is all right, it took me about a week to get Hollywood out of my lungs, but I am still writing all right, I believe. The hell of it though, letting me get my hand into it, as was, your material was getting too long; now all you have is still more words. But I think this belongs in your volume. What about dropping DEATH DRAG, if something must be eliminated? That was just a tale, could have happened anywhere, could have been printed as happening anywhere by simply changing the word Jefferson where it occurs, once only I think.

Let me know what you think of this. I think it is really pretty good, to stand as it is, as a piece without implications. Maybe I am just happy that that damned west coast place has not cheapened my soul as much as I probably believed it was going to do.

The completion of that “Appendix,” as Faulkner decided to call it, was an event in his career as a novelist. It became an integral part of The Sound and the Fury and was the last change he was to make in what remained his favorite among his own works. Years later he would say, in the extraordinary interview he gave to Jean Stein for the Paris Review:

Since none of my work has met my own standards, I must judge it on the basis of that one which caused me the most grief and anguish, as the mother loves the child who became the thief or murderer more than the one who became the priest.

INTERVIEWER: What work is that?

FAULKNER:The Sound and the Fury. I wrote it five separate times, trying to tell the story, to rid myself of the dream which would continue to anguish me until I did. It’s a tragedy of two lost women: Caddy and her daughter. Dilsey is one of my favorite characters, because she is brave, courageous, generous, gentle, and honest. She’s much more brave and honest and generous than me.

INTERVIEWER: How did The Sound and the Fury begin?

FAULKNER: It began with a mental picture. I didn’t realize at the time it was symbolical. The picture was of the muddy seat of a little girl’s drawers in a pear tree, where she could see through a window where her grandmother’s funeral was taking place and report what was happening to her brothers on the ground below. By the time I explained who they were and what they were doing and how her pants got muddy, I realized it would be impossible to get all of it into a short story and that it would have to be a book. And then I realized the symbolism of the soiled pants, and that image was replaced by the one of the fatherless and motherless girl climbing down the rainpipe to escape from the only home she had, where she had never been offered love or affection or understanding.

I had already begun to tell the story through the eyes of the idiot child, since I felt that it would be more effective as told by someone capable only of knowing what happened, but not why. I saw that I had not told the story that time. I tried to tell it again, the same story through the eyes of another brother. That was still not it. I told it for the third time through the eyes of the third brother. That was still not it. I tried to gather the pieces together and fill in the gaps by making myself the spokesman. It was still not complete, not until fifteen years after the book was published, when I wrote as an appendix to another book the final effort to get the story told and off my mind, so that I myself could have some peace from it. It’s the book I feel tenderest towards. I couldn’t leave it alone, and I never could tell it right, though I tried hard and would like to try again, though I’d probably fail again.

In this instance Faulkner didn’t try again, as he had actually tried in other instances — for example, in Big Woods (1955), which is partly a recasting of Go Down, Moses (1942) — but the truth is that his Appendix had brought him closer to success, even by his own impossible standards, than he acknowledged in the interview. After one reads the Compson genealogy, the whole book does fall into pattern “like a jigsaw puzzle when the magician’s wand touched it.” What seems extraordinary is that he wrote the genealogy sixteen, not fifteen, years after publishing The Sound and the Fury, and at a time when he did not own a copy of his favorite novel. The works might disappear from his shelves and even from the secondhand bookstores, but the story lived completely in his mind.

Moreover, it was linked with stories presented in other books, some of which, in that autumn of 1945, were still to be written. The power and persistence of his imagination was (not “were,” for power and persistence must be regarded here as related aspects of the same quality) what made him unique among the novelists of his century. Soon I would try, without success, to describe the quality in my introduction to the Portable. “All his books in the Yoknapatawpha saga,” I would say, “are part of the same living pattern. It is this pattern, and not the printed volumes in which part of it is recorded, that is Faulkner’s real achievement. Its existence helps to explain one feature of his work: that each novel, each long or short story, seems to reveal more than it states explicitly and to have a subject bigger than itself. All the separate works are like blocks of marble from the same quarry: they show the veins and faults of the mother rock. Or else — to use a rather strained figure — they are like wooden planks that were cut, not from a log, but from a still living tree. The planks are planed and chiseled into their final shapes, but the tree itself heals over the wound and continues to grow.” Like a tree, the Compson story had continued to grow, striking roots into the past — as deep as the battle of Culloden — and raising branches into what had been the future when the published novel ended on Easter morning, 1928. That was the morning when it was discovered that Caddy’s daughter, Quentin, the younger of Faulkner’s “two lost women,” had run off with a carnival pitchman after breaking open her Uncle Jason’s strongbox — “And so vanished,” Faulkner tells us in his Appendix. It is a way of saying that although she was the last of the Compsons, nothing in her subsequent career had touched his imagination. But the other lost woman, Quentin’s mother, he had always regarded with a mixture of horror and unwilling affection. Therefore he follows her to 1943, when she is living in occupied France as a German general’s mistress, “ageless and beautiful, cold serene and damned.”

It was in this fashion that the story lived in Faulkner’s mind, where it grew and changed like every living thing. The more I admired his Appendix, the more I found that some of the changes raised perplexing questions. Where, for example, did Jason keep his strongbox? — under a loose board in the clothes closet, as the novel tells us, or in a locked bureau drawer, as I read in the new manuscript? How much money was in the box? — three thousand dollars, as Jason informed the sheriff in the novel, or nearly seven thousand, as in the Appendix? — where I also learned that $2840.50 of the larger sum had been saved by Jason himself “in niggard and agonized dimes and quarters and halfdollars”; the novel had implied that all the money in the box was stolen from his niece. How did Quentin escape from Jason’s locked room? — did she climb down a pear tree (novel) or slide down a rainspout (Appendix)? Was it Luster or TP (or both) who bounced golf balls against the smokehouse wall? and which of the two Negro boys was older? And what about Jason Compson? — is he altogether repellent and hateful, as in the novel, or should we think of him as having a certain redeeming doggedness and logic, as the Appendix suggests?

Faulkner had challenged me, as it were, to find “discrepancies . . . too glaring to leave in,”and it seemed to me that there were more than a few. I wrote him that since I couldn’t undertake to remove the discrepancies, I would shortly return the manuscript for whatever changes Faulkner thought best to make. He answered immediately.

[Oxford]

Saturday. [October 27, 1945]

Dear Cowley:

Letter received. I hope this catches you before you have returned the ms. . . . Jason would call $2840.50 ‘$3000.00’ at any time the sum was owed him. He would have particularised only when he owed the money. He would have liked to tell the police she stole $15,000.00 from him, but did not dare. He didn’t want the money recovered, because then the fact that he had stolen $4000.00 from the thief would have come out. He was simply trying to persuade someone, anyone with the power, to catch her long enough for him to get his hands on her.

(In fact, the purpose of this genealogy is to give a sort of bloodless bibliophile’s point of view. I was a sort of Garter King-at-Arms, heatless, not very moved, cleaning up “Compson” before going on to the next “C-o" or “C-r”.)

Re Benjy. This Garter K/A didn’t know about the monument and the slipper. He knew only what the town could have told him: a) Benjy was an idiot. b) spent most of his time with a negro nurse in the pasture, until the pasture was deeded in the County Recorder’s office as sold. c) was fond of his sister, could always be quieted indoors when placed where he could watch firelight. d) Was gelded by process of law, when and (assumed) why, since the little girl he scared probably made a good story out of it when she got over being scared.

My attitude toward Benjy and Jason has not changed. . . .

Ignorant as I was of heraldic terms, I consulted the Britannica and found that the Garter King of Arms presides over the Heralds’ College, or College of Arms, which rules on questions having to do with armorial bearings and pedigrees. Faulkner had often written as if the author too were an imagined character, and the Garter King of Arms was his latest avatar. Besides providing him with a fresh approach to the Compson story, his new role had another great advantage. “This Garter K/A,” as Faulkner said, “. . . knew only what the town could have told him.”Presumably he hadn’t read The Sound and the Fury, and his ignorance might serve as an excuse for the discrepancies in his narrative.

In that case, however, Faulkner himself was indirectly apologizing for an apparent weakness that was also his strongest quality as a novelist. His creative power was so unflagging that he could not tell a story twice without transforming one detail after another. He waved his magician’s wand, and a pear tree in blossom was metamorphosed into a rainspout. He waved the wand again, and four thousand additional dollars appeared in Jason’s strongbox, while the box itself, after vanishing from a closet, materialized in a locked bureau drawer. That was easy for him, but I was merely an editor, not a magician, and what was I to say about His text? In retrospect the situation impresses me as a high comedy of misunderstanding. Here was Faulkner striding ahead in his imperial fashion, finding the same sort of excuses for violating the laws of consistency that an emperor finds for invading the realm of a neighboring kinglet; and here was I admiring his boldness, but still mildly objecting that he had told a somewhat different story in the published novel, that the pear tree should still be in blossom, and that Jason was more of a villain than the Appendix made him seem.

The pedantry and the caution were imposed on me by my role as editor, but I still blame myself for one sort of obtuseness. I should have realized from the beginning that, as Faulkner was to tell me in a subsequent letter, the true Compson story was the one that lived and grew in his imagination. The published book contained only what he had known about the story in 1929; in other words, only part of the truth. If I had offered to change everything in the published novel that did not agree with the Appendix, I suspect that Faulkner would have encouraged me in the undertaking. It was vastly different, however, when I urged him to change the Appendix and make it agree with the published book, for that would have meant going back to an earlier time when he had known or invented much less about the Compson family.

DURING the next month, while I worked on the introduction, most of my correspondence was concerned with two subjects. One of them was Faulkner’s map of Yoknapatawpha County; the other was the descriptive text to be printed on the jacket of the Portable. On those two subjects I exchanged more letters with the Viking Press than I did with Faulkner.

Marshall Best wrote me about the map on November 20, 1945. “I am sure we can get it in somehow,” he said. “If Faulkner would draw a new map it would be an added touch. If so, he might make it with less text on it, keeping only what is appropriate to this volume and thereby making it more legible.” Then, after consulting with the production department, he added, “Better let us have the lettering done as his is not very legible. . . . We will use it as an endpaper turned sideways. I am returning the map as you may not have a copy.”

I promptly forwarded the map to Faulkner.

In the same letter Marshall broached the second topic. “I enclose rough copy for the front of the jacket,” he said. “Is this what we ought to say and have the right to say?” His rough copy read:

THE PORTABLE FAULKNER

The saga of Yoknapatawpha County, Mississippi (1820-1945) — in effect, a new work by William Faulkner, drawn from his best published novels and short stories, with connective material and notes on the characters supplied by himself.

I did not think that this was quite what we ought to say, and I exchanged letters with Marshall on the subject. Also I had sent the proposed wording to Faulkner and said that I questioned the phrase “in effect, a new work by William Faulkner.”

In the same letter I had mildly complained about the lack of biographical details. There was hardly anything in Who’s Who except the place and date of his birth (b. New Albany, Miss., Sept. 25, 1897) and the titles of his books. The sketch was followed by an asterisk, to signify — in the special language of the editors — “that either the published biography could not be verified, or that at least temporary non-currency in respect to general reference interest has been indicated by lack of change in the data or failure to receive requested information.” I translated: Faulkner hadn’t been answering letters from Who’s Who. He was listed as William Falkner, without a “u.” What, I asked, was the proper spelling of his name?

Once again he answered my questions at length.

[Oxford]

Saturday. [December 8, 1945]

Dear Cowley:

You should have the map by now.

You are right, the phrase wont do, out of regard to Random House. Could it read something like this:

. . . saga of . . . county . . .alt;br/A chronological picture of Faulkner’s apocryphal Mississippi county, selected from his published works, novels and stories, with a heretofore unpublished genealogy of one of its principal families.

Edited by M. Cowley

It’s not a new work by Faulkner: It’s a new work by Cowley all right through. If you like, you might say “the first chronological picture” etc.

The name is “Falkner”. My great-grandfather, whose name I bear, was a considerable figure in his time and provincial milieu. He was prototype of John Sartoris: raised, organised, paid the expenses of and commanded the 2nd Mississippi Infantry, 1861-2, etc. Was a part of Stonewall Jackson’s left at 1st Manassas that afternoon; we have a citation in James Longstreet’s longhand as his corps commander after 2nd Manassas. He built the first railroad in our county, wrote a few books, made grand European tour of his time, died in a duel and the county raised a marble effigy which still stands in Tippah County. The place of our origin shows on larger maps; a hamlet named Falkner just below Tennessee line on his railroad.

My first recollection of the name was, no outsider seemed able to pronounce it from reading it, and when he did pronounce it, he always wrote the “u” into it. So it seemed to me that the whole world was trying to change it, and usually did. Maybe when I began to write, even though I thought then I was writing for fun, I secretly was ambitious and did not want to ride on grandfather’s coat-tails, and so accepted the “u", was glad of such an easy way to strike out for myself. I accept either spelling. In Oxford it usually has no “u” except on a book. The above was always my mother’s and father’s version of why I put back into it the “u” which my greatgrandfather, himself always a little impatient of grammar and spelling both, was said to have removed. I myself really dont know the true reason. It just seemed to me that as soon as I got away from Mississippi, I found the “u” in the word whether I wished it or not. I still think it is of no importance, and either one suits me.

I graduated from grammar school, went two years to highschool, but only during fall to play on the football team, my parents finally caught on, worked about a year as a book-keeper in grandfather’s bank, went to RAF, returned home, attended I year at University of Mississippi by special dispensation for returned troops, studying European languages, still didn’t like school and quit that. Rest of education undirected reading.

The above I still hope can remain private between you and me, the facts are in order and sequence for you to use, to clarify the whos who piece. The following is for your ear too. What I have written is of course in the public domain and the public is welcome; what I ate and did and when and where, is my own business.

I more or less grew up in my father’s livery stable. Being the eldest of four boys, I escaped my mother’s influence pretty easy, since my father thought it was fine for me to apprentice to the business. I imagine I would have been in the livery stable yet if it hadn’t been for motor car.

When I came back from RAF, my father’s health was beginning to fail and he had a political job: business manager of the state University, given to him by a countryman whom my grandfather had made a lawyer of, who became governor of Mississippi. I didn’t want to go to work; it was by my father’s request that I entered the University, which I didn’t want to do either. That was in 1920. Since then I have: Painted houses. Served as a 4th class postmaster. Worked for a New Orleans bootlegger. Deck hand in freighters (Atlantic). Hand in a Gulf of Mexico shrimp trawler. Stationary boiler fireman. Barnstormed an aeroplane out of cow pastures. Operated a farm, cotton and feed, breeding and raising mules and cattle. Wrote (or tried) for moving pictures. Oh yes, was a scout master for two years, was fired for moral reasons. [That is, because he was the author of Sanctuary.]

I wondered what Faulkner would say after reading my introduction. I hoped he would like it. I believed, though not confidently, that he would like it. And he did like most of it, as I was soon to learn; he even accepted my reservations about his work. I had felt that it was necessary, however, to include a few biographical details, not those he had told me in confidence, but others, not always accurate, that I had gathered from the sources available in New York. To these details, true or false, he objected strongly, and they would become the subject of a protracted discussion that had its comic overtones.

AMONG the writers of his time, Faulkner was altogether exceptional in the value that he placed on privacy. It was not that he had a great secret, or more than the usual quota of little secrets; it was simply that he could not bear to have his personal affairs discussed in print. To find anything like his feeling in that respect, one would have to go back to Henry James and the abhorrence for published gossip that he expressed in short novels like The Reverberator and The Aspern Papers. But again like James, though in a fashion of his own, Faulkner had a habit of doing and saying things that made good stories and that proved to be the crack in his armor. The stories were repeated by his friends to strangers and by strangers to newspaper columnists, often with an embroidery of details, until at last they were printed as largely erroneous accounts. These Faulkner seldom read, and apparently he made a principle of never correcting them, with the result that the errors became sanctified by repetition.

In my search for dependable information I had turned to a useful reference work, Twentieth Century Authors (1942). It was edited by Stanley J. Kunitz and Howard Haycraft, with some concern for accuracy in a field where legends abound, but the conflicting stories about Faulkner had proved too much for them. For example, their account of his wartime activities is a short paragraph containing, as I afterward learned, at least five misstatements of fact. It reads:

The First World War woke him from this lethargy. Flying caught his imagination, but he refused to enlist with the “Yankees,” so went to Toronto and joined the Canadian Air Force, becoming a lieutenant in the R.A.F. Biographers who say he got no nearer France than Toronto are mistaken. He was sent to France as art observer, had two planes shot down under him, was wounded in the second shooting, and did not return to Oxford until after the Armistice.

I wanted to accept that paragraph because I had come to think of Faulkner, perhaps rightly, as being among the “wounded writers” of his generation, with Hemingway and others. It was hard for me to believe that his vivid stories about aviators in France — “Ad Astra,” “Turnabout,” “All the Dead Airmen” — and his portraits of spiritually maimed veterans, living corpses, in Soldier’s Pay and Sartoris, were based on anything but direct experience. At the same time I wanted to follow his wishes by giving no more than the necessary bare details of his life. So I had mentioned his wartime adventures at the very beginning of my introduction, but had disposed of them in only three sentences:

“When the war was over—the other war — William Faulkner Went back to Oxford, Mississippi. He had been trained as a flyer in Canada, had served at the front in the Royal Air Force, and, after his plane was damaged in combat, had crashed it behind the British lines. Now he was home again and not at home, or at least not able to accept the postwar world.”

What I did not realize was that my second sentence, rewritten as it was from the paragraph in Twentieth Century Authors, included three of the misstatements. There was nothing right in it except that Faulkner had been trained as a flier in Canada. Still, I did not dream that mv facts were wrong or that Faulkner would question them. I was worried, however, by some reservations I had offered on a later page about his prose style. I had conjectured that its faults were due partly to his always having worked in solitude. In this connection I had quoted some remarks made by Henry James in his little book about Hawthorne. “Great things,” James says, “have of course been done by solitary workers; but they have usually been done with double the pains they would have cost if they had been produced in more genial circumstances. The solitary worker loses the profit of example and discussion; he is apt to make awkward experiments; he is in the nature of the case more or less of an empiric. The empiric may, as I say, be treated by the world as an expert; but the drawbacks and discomforts of empiricism remain to him and are in fact increased by the suspicion that is mingled with his gratitude, of a want in the public taste of a sense of the proportion of things.” After quoting from James, I had continued:

“Like Hawthorne, Faulkner is a solitary worker by choice, and he has done great things not only with double the pains to himself that they might have cost if produced in more genial circumstances, but sometimes also with double the pains to the reader. Two or three of his books as a whole and many of them in part are awkward experiments. All of them are full of overblown words like ‘imponderable,’‘immortal,’ ‘immutable,’and ‘immemorial’ that he would have used with more discretion, or not at all, if he had followed Hemingway’s example and served an apprenticeship to an older writer. He is a most uncertain judge of his own work, and he has no reason to believe that the world’s judgment is any more to be trusted; indeed, there is no American writer who would be justified in feeling more suspicion of ‘a want in the public taste of a sense of the proportion of things.'”

What would Faulkner say about iny strictures? In his first letter after reading the introduction, he said nothing at all about them, though later he was to discuss them briefly. He perturbed me, however, by objecting to my mention of his wartime experiences.

[Oxford]

Monday. [December 24, 1945]

Dear Clowley:

The piece received, and is all right. I still wish you could lead off this way:

When the war was over — the other war — William Faulkner, at home again in Oxford, Mississippi, yet at the same time was not at home, or at least not able to accept the postwar world.

Then go on from there. The piece is good, thoughtful, and sound. I myself would have said here:

“or rather what he did not want to accept was the fact that he was now twenty-one years old and therefore was expected to go to work.”

But then, that would be my piece and not yours. It is very fine and sound. I only wish you felt it right to lead off as above, no mention of war experience at all.

Best season’s greetings and wishes. I hope to see you some day soon, thank you for this job.

Why didn’t he say flatly that he hadn’t served in France during the war? I suspect that he was adhering to his fixed principle of never correcting misstatements about himself, though at the same time he was determined not to let these particular misstatements stand at the head of my introduction to his work. I was slow to catch the point, however, and I answered his letter by explaining briefly that some mention of his wartime experiences seemed essential if the reader was to understand his rebellion against the post-war world.

In an undated letter that must have been written in the first days of January, 1946, Faulkner answered my questions in his own fashion. But first he returned to the topic of what should or shouldn’t be said about his part in World War I.

Dear Cowley:

Herewith returned [the text of the introduction], with thanks. It’s all right, sound and correct and penetrating. I warned you in advance I would hope for no biography, personal matter, at all. You elaborate certain theses from it, correctly I believe too. I just wish you didn’t need to state in the piece the premises you derive from. If you think it necessary to include them, consider stating a simple skeleton, something like the thing in Who’s Who; let the first paragraph, Section Two, read, viz:

Born (when and where). (He) came to Oxford as a child, attended Oxford grammar school without graduating, had one year as a special student in modern languages in the University of Mississippi. Rest of education was undirected and uncorrelated reading. If you mention military experience at all (which is not necessary, as I could have invented a few failed RAF airmen as easily as I did Confeds) say “belonged to RAF 1918.” Then continue: Has lived in same section of Miss, since, worked at various odd jobs until he got a job writing movies and was able to make a living at writing.

Then pick up paragraph 2 of Section II and carry on. I’m old-fashioned and probably a little mad too; I dont like having my private life and affairs available to just any and everyone who has the price of the vehicle it’s printed in, or a friend who bought it and will lend it to him. I’ll be glad to give you all the dope when we talk together. Some of it’s very funny. I just dont like it in print except when I use it myself, like old John Sartoris and old Bayard and Mrs. Millard and Simon Strother and the other Negroes and the dead airmen.

I dont see too much Southern legend in it [the introduction]. I’ll go further than you in the harsh criticism.

The style, as you divine, is a result of the solitude, and granted a bad one. It was further complicated by an inherited regional or geographical (Hawthorne would say, racial) curse. You might say, studbook style: “by Southern Rhetoric out of Solitude” or “Oratory out of Solitude”. . . .

Thank you for seeing the piece. It’s all right. The “writing in solitude” is very true and sound. That explains a lot about my carelessness about bad taste. I am not always conscious of bad taste myself, but I am pretty sensitive to what others will call bad taste. I think I have written a lot and sent it off to print before I actually realised strangers might read it.

I was dismayed by Faulkner’s suggestion that I should omit the whole first part of the introduction; that would cost me four pages of text in which I had made what seemed to me important statements about his work. Still slow to catch the point, I wrote to explain once again why I thought it was necessary to mention his activities in wartime. Then I went back to work on some editorial notes for the book. A few days later I received the only stern letter that Faulkner wrote me.

[Oxford]

Monday. [January 21, 1946]

Dear Cowley:

Yours at hand. You’re going to bugger up a fine dignified distinguished book with that war business. The only point a war reference or anecdote could serve would be to reveal me a hero, or (2) to account for the whereabouts of a male of my age on Nov. 11, 1918 in case this were a biography. If, because of some later reference back to it in the piece, you cant omit all European war reference, say only what Who’s Who says and no more:

Was a member of the RAF in 1918.

I’ll pay for any resetting of type, plates, alteration, etc. . . .

I’m really concerned about the war reference. As I said last, I’m going to be proud of this book. I wouldn’t have put in anything at all about the war or any other personal matter.

This time I saw the light. In a letter to the Viking Press, I asked them to delete the statement that Faulkner’s plane had been damaged in combat. It was too late to make extensive changes, but Faulkner was relieved by the correction of this one gross error. He wrote:

[Oxford]

Friday. [February 1, 1946]

Dear Cowley:

Yours of 26th at hand. I see your point now about the war business, and granting the value of the parallel you will infer, it is “structurally” necessary. I dont like the paragraph because it makes me out more of a hero than I was, and I am going to be proud of your book. The mishap was caused not by combat but by (euphoniously) “cockpit trouble”; i.e., my own foolishness: the injury I suffered I still feel I got at bargain rates. A lot of that sort of thing happened in those days, the culprit unravelling himself from the subsequent unauthorised crash incapable of any explanation as far as advancing the war went, and grasping at any frantic straw before someone in authority would want to know what became of the aeroplane, would hurry to the office and enter it in the squadron records as “practice flight”. As compared with men I knew, friends I had and lost, I deserve no more than the sentence I suggested before: “served in (or belonged to) RAF”. But I see where your paragraph will be better for your purpose, and I am sorry it’s not nearer right. . . .

I sent him a revised first paragraph of my introduction, with the account of his military service reduced to ten accurate words: “He had served in the Royal Air Force in 1918.”

[ Oxford]

Monday. [February 13. 1946]

Dear Brother:

I feel much better about the book with your foreword beginning as now. I saw your point about (and need for) the other opening all the time. But to me it was false. Not factually, 1 dont care much for facts, am not much interested in them, you cant stand a fact up, you’ve got to prop it up, and when you move to one side a little and look at it from that angle, it’s not thick enough to cast a shadow in that direction. But in truth, though maybe what I mean by truth is humility and maybe what I think is humility is immitigable pride, I would have preferred nothing at all prior to the instant I began to write, as though Faulkner and Typewriter were concomitant, coadjutant and without past on the moment they first faced each other at the suitable (nameless) table. ... I dont want to read TSAF again [I had sent him my treasured copy of the novel]. Would rather let the appendix stand with the inconsistencies, perhaps make a statement (quotable) at the end of the introduction, viz.: The inconsistencies in the appendix prove to me the book is still alive after 15 years, and being still alive is growing, changing; the appendix was done at the same heat as the book, even though 15 years later, and so it is the book itself which is inconsistent: not the appendix. That is, at the age of 30 I did not know these people as at 45 I now do; that I was even wrong now and then in the very conclusions I drew from watching them, and the information in which I once believed. . . .

The book was printed and bound copies were ready by the middle of April. The author wrote me a few days later.

[Oxford]

Tuesday. [April 23, 1946]

Dear Cowley:

The job is splendid. Damn you to hell anyway. But even if I had beat you to the idea, mine wouldn’t have been this good. By God, I didn’t know myself what I had tried to do, and how much I had succeeded.

I am asking Viking to send me more copies (I had just one) and I want to sign one for you, if you are inclined. Spotted horses is pretty funny, after a few years.

Random House and Ober [Faulkner’s literary agent] lit a fire under Warner, I dont know how, and I am here until September anyway, on a dole from Random House, working at what seems now to me to be my magnum o.

It was the handsomest letter of acknowledgment I had ever received. But the treasure I have saved from those days is the copy of The Sound and the Fury that I sent him because he had no copy of his own. It came back with an inscription:

To Malcolm Cowley—

Who beat me to what was to have been the leisurely pleasure of my old age.

William Faulkner

IN October, 1948, he published a new book, the first since Go Down, Moses in 1942 (though meanwhile not a few of the earlier books had been reissued). The new one was Intruder in the Dust, and I reviewed it for the New Republic. I said that the story, or rather the sermon that one of the characters, Gavin Stevens, interpolated into the story, revealed the dilemma of Southern nationalism. “The tragedy of intelligent Southerners like Stevens (or like Faulkner),” I concluded, “is that their two fundamental beliefs, in equal justice and in Southern independence (or simple identity), are now in violent conflict.”

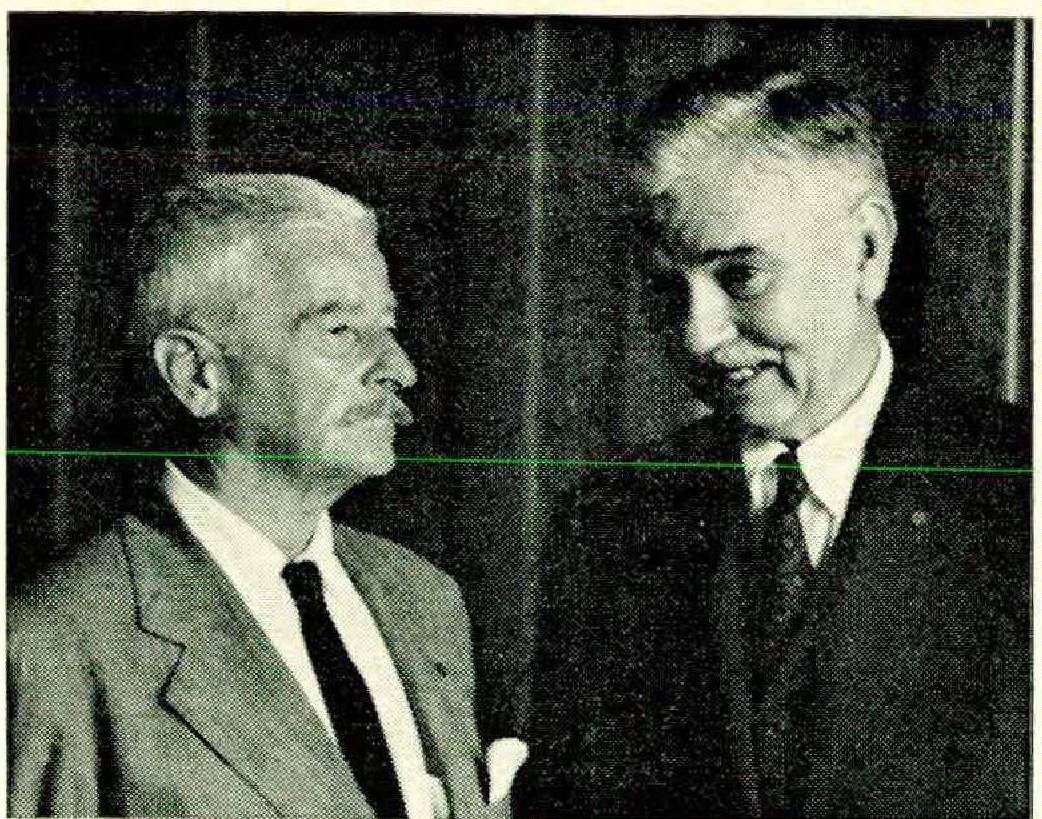

Toward the end of the month Faulkner made his long-promised visit to New York. My wife and I were invited to a dinner given to celebrate his arrival. That would be our first meeting.

When I was working on a profile of Hemingway in the summer of 1948, my editor at Life, Robert Goughian, had asked me whether I would undertake a companion piece on Faulkner. “That depends,” I said, “on whether Faulkner consents to have it written. I’ll ask him when he comes to New York, and in the meantime. I’ll start collecting material.”

Accordingly, I made some very long entries in my notebook during Faulkner’s October visit. Here I shall set them down without correcting some errors and repetitions.

Sunday, October 23. — This week William Faulkner has been in NY. There was a dinner for him Tuesday evening at the Park Avenue apartment of Robert Haas [a partner in Random House] — a dinner with two butlers hired for the occasion, one of those dinners in style (though nobody dressed) where the ladies withdraw as they did fifty years ago and leave the gentlemen discoursing over cigars and cognac. There was a good deal of cognac. Muriel [my wife] and I left at two in the morning, but it seems that Faulkner and Eric Devine and perhaps one or two others adjourned to Hal Smith’s apartment.

Faulkner is a small man (5 ft. 5, I should judge), very neatly put together, slim and muscular. Small, beautifully shaped hands. His face has an expression like Poe’s in photographs, crooked and melancholy. But his forehead is low, his nose Roman, and his gray hair forms a low wreath around his forehead, so that he also looks like a Roman emperor. Bushy eyebrows; eyes deeply set and with a droop at the outer corners; a bristly mustache. He stands or walks with an air of great dignity and talks — tells stories — in a strong Mississippi accent.

Very modest. Takes suggestions if they are offered in good part. Has a Southerner’s extremely good manners. Also has an extreme sense of privacy. Doesn’t want his private life in the public prints.

I remember setting down those notes on a gray and shivery Sunday morning. That afternoon I drove to New York, saw Faulkner again, and brought him back with me to our house in Sherman. Among other subjects, we talked about the profile of him that Life had asked me to do. I thought it should deal chiefly with his work, and that the biographical details might be limited to those already published in magazines or newspapers. Faulkner wasn’t happy about the intrusion into his life, modest and circumspect as it promised to be, but when we went back to the subject, after lunch on Tuesday, he gave what I interpreted as a sigh of resigned assent.

It was a magnificent fall afternoon. The maples had lost most of their leaves, but the oaks still wore an imperial purple. We went for a long drive across the foothills of the Taconic Range into the Harlem Valley, which is like a continuation northward of the Shenandoah. Between comments on the landscape, Faulkner brought forth a good deal of information about himself, as if to help along my project. He continued to talk about himself that evening, and some of the information went into the next entry in my notebook.

October 26, Faulkner again. — He’s gone now, by train for New York. . . . I want to set down a few of the things he told us (1) about his life in Oxford and New Orleans after the war, and his first book; (2) about the South; (3) about writing.

1. After the war he traveled around the country with a friend and drinking companion who was the receiver for a big bankrupt lumber company. Sometimes he was called an assistant, sometimes a secretary, and he was about to go to Cuba as an interpreter (he didn’t know Spanish) when Stark Young told him that he ought to try living in NY and promised to get him a job at Lord & Taylor’s bookstore. He worked there several months for $11 a week. . . . Then he got a letter from home telling him that he had been appointed postmaster.

After working as postmaster for about two years, he went to New Orleans and became a rum runner. He ran a cabin cruiser out to where he got the alcohol, took it into the city through bayous, and delivered it to the back room of an Italian restaurant. There the proprietor’s mother, a woman of 80, took charge of it and gave it the proper flavors: laudanum, if it was to be called Scotch, and creosote, if it was to be rye. She couldn’t read, but she knew the labels by the looks of them.

In New Orleans he met his old boss at Lord & Taylor’s, Elizabeth Prall, and found that she was now Mrs. Sherwood Anderson. He used to go walking with Anderson in the afternoon and drink with him all night. He thought, “If this is the way a writer lives, I want to be a writer.” He told Mrs. Anderson that he was writing a book. She said, “Don’t you ask Sherwood to read it.” Then she said, “But I’ll read it,” and he finally gave her the ms. Before that time Sherwood had said, expecting his publisher in New Orleans, ”If you promise that I won’t have to read it, I’ll make Horace Liveright publish it.”

Bill went for a walking trip in France and Italy. When he was back in Paris, broke, he got a letter from Liveright with a check lor $200, his advance. Nobody would cash the check for him. The American consul told him to send it back to Liveright and ask for a draft. But he went to the British consul, showed him his British army dogtag, and the consul gave him the $200. When he got back to Oxford the book, Soldier’s Pay, had been published and forgotten.

He says that he commenced with the idea that novels should deal with imaginary scenes and people — so Soldier’s Pay was laid in Georgia, where he had never been. With Sartoris, his third novel, he began to create Yoknapatawpha County. He started with the characters: then they required a background, which he imagined, and the background suggested other characters. When he was writing The Sound and the Fury, he found there were connections between the Sartoris family and the Compsons, and from that point the county continued to grow. Several times its location has shifted a few miles westward. It borrows scenes and features from three real Mississippi counties.

2. The South. — “Mississippi is still the frontier,” he says. “In Mississippi an officer of the law can’t go around without a gun where he can reach it fast, because he never knows when he’s going to need it.” The Southern or frontier way, he says, is to have not enough, but always more than enough, enough to waste. Cut down a tree to make a linchpin.

Speaking of the Southern sense of family, “That’s also a memory of the frontier. It goes back to the days when kin were all you had to depend on for help, because you couldn’t depend on the law. But it’s also a memory of the Highland clans.” . . .

. . . We talked about Intruder in the Dust, though without mentioning my review; I assumed that he hadn’t read it. Still, what he said about Gavin Stevens may have been an indirect answer to my interpretation of the novel. Stevens, he explained, was not speaking for the author, but for the best type of liberal Southerners; that is how they feel about the Negroes. “If the race problems were just left to the children,” Faulkner told me, “they’d be solved soon enough. It’s the grown-ups and especially the women who keep the prejudice alive.”

His farm is run by the three Negro tenant families, in which there are five hands. He lets them have the profits, if any, because — he said, speaking very softly — “The Negroes don’t always get a square deal in Mississippi.” He figures that his beef costs him $5 a pound. . . .

3. On writing. “Get it down. Take chances. It may be bad, but that’s the only way you can do anything really good.”

“Wolfe took the most chances, although he didn’t always know what he was doing. I come next and then Dos Bassos. Hemingway doesn’t take chances enough.”

Faulkner works when he feels like working, sometimes for 12 or 13 hours a day. Usually he works in the morning, but when the mood is on him he works in the afternoons too, and at night. I think he writes in pencil, then copies and corrects on a very old typewriter (see his story of how he wrote As I Lay Dying on the bottom of a wheelbarrow). “Some time you’ve got to go to work and finish it,” he said.

That was in the evening after our return from the Harlem Valley. He got out of his chair and began pacing up and down the living room. With his short steps and small features, he gave an impression of delicacy, fastidiousness, but also of humility combined with almost Napoleonic pride. “My ambition is to put everything into one sentence,” he said. “Not only the present but the whole past on which it depends and which keeps overtaking the present, second by second.” He went on to explain that in writing his prodigious sentences he is trying to convey a sense of simultaneity, not only giving what happened in the shifting instant, but everything that went before and made the quality of that instant. . . .

He said that his mother wanted him to be a painter. Sometimes he does paint a little, not with a brush — “I have no patience for that” — but with a kitchen knife. If he had the money he would hire a fresco painter to do some of the scenes in his books — for example, the Ghickasaws dragging the steamboat through the woods on rollers, while The Man sits on deck in the red shoes too small for his feet (as in “A Justice”), or the scene from Absalom, Absalom! in which the French architect, hiding in a swamp, is discovered and held cowering in a circle of torches by Sutpen and his half-naked slaves. . . .

I remember two of the remarks about writing that he made on the long drive to the station. In regard to style he said, “There are some kinds of writing that you have to do very fast, like riding a bicycle on a tightrope.” Later I mentioned Hawthorne’s complaint about the devil who got into his inkpot. “I listen to the voices,” Faulkner told me, “and when I put down what the voices say, it’s right. Sometimes I don’t like what they say, but I don’t change it.”

I wondered what Faulkner would say when he saw my Hemingway profile, which was published early in 1949. It was, as I had told him, a straightforward account of Hemingway’s career, about which I had gathered a good deal of unfamiliar material; I was reasonably satisfied with what I had written. But the text was surrounded, submerged, and. it seemed to me, changed in import by a collection of intimate photographs, beginning with a full-page portrait of Hemingway in his bedroom at half past six in the morning with five of his favorite cats: he looms behind them, bare-footed, barethighed, bare-chested, while he meditatively sprinkles salt on his breakfast egg. There were also photographs of Hemingway’s four wives, who, by an inspiration of the makeup department, were candidcameraed on facing pages: look and compare. I was hardly surprised by Faulkner’s comment when it finally arrived.

Oxford, Friday. [February 11, 1949]

Dear Malcolm:

I saw the LIFE with your Hemingway piece. I didn’t read it but I know it’s all right or you wouldn’t have put your name on it; for which reason I know Hemingway thinks it’s all right and I hope it will profit him — if there is any profit or increase or increment that a brave man and an artist can lack or need or want.

But I am more convinced and determined than ever that this is not for me. I will protest to the last: no photographs, no recorded documents. It is my ambition to be, as a private individual, abolished and voided from history, leaving it markless, no refuse save the printed books; I wish I had had enough sense to see ahead thirty years ago and, like some of the Elizabethans, not signed them. It is my aim, and every effort bent, that the sum and history of my life, which in the same sentence is my obit and epitaph too, shall be them both: He made the books and he died. . . .

FAULKNER died in July, 1962, almost exactly a year after Hemingway, eight months after James Thurber, and a few weeks before E. E. Cummings. Those were all great losses, and, with earlier ones, they completely changed the literary landscape.

I think of their generation, which is also mine, as it started out many years ago. It was a generation like any other, I suppose, but it included what seems to be an extraordinary assortment of literary personalities. Of course the truth may be that the personalities, which might exist in any generation — which probably do exist there, by the law of averages — were given an extraordinary freedom to develop by the circumstances of the time. We started to publish in the post-war years, when our youth in itself was a moral asset. People seemed to feel that an older generation had let the world go to ruin, and they hoped that a new one might redeem it. The public was as grandly hospitable to young writers as it was to young movie actors and financiers just out of Yale. Scott Fitzgerald was a best-selling novelist at twenty-four, and Glenway Wescott at twenty-seven. Hemingway, Dos Passos, Wilder, and Wolfe were all international figures at thirty. Even Faulkner, though slower to be recognized than the others, was a famous author in France while he was being neglected at home.

The generation had, like any other, a particular sense of life, which it was determined to express in books. Perhaps it felt more confidence than other generations have felt in its ability to make the books completely new. Everything in American literature seemed to be starting afresh. Every possibility seemed to be opening for the first time (since in those days we were splendidly ignorant of the American literary past), and almost any achievement seemed feasible. “I want to be one of the greatest writers who have ever lived, don’t you?” Fitzgerald said to Edmund Wilson not long after they got out of Princeton. Wilson thought the remark was rather foolish, but he shared some of the feeling that lay behind it, as obviously Hemingway and Faulkner did. They all had a sense of being measured against the European past — against the future, too — and of being called upon to do not only their best but something mysteriously better that could be done “without tricks and without cheating,” as Hemingway said, if a writer was serious enough and had luck on his side.

Fortunate in the beginning, the generation was fortunate again after World War II. Most of the new writers who appeared in the 1950s were less adventurous than their predecessors had been in the realm of imaginative art, perhaps because their critical sense was more exacting and inhibiting. They were given to writing critical studies, and the subject of these, in many cases, was the books that Faulkner and other famous men of his time had written twenty or thirty years before. Thus, in middle age the generation had the privilege of basking in a warm critical afterglow. Even its less prominent members acquired a sense of reassurance from the presence of their great contemporaries. Their world was like a forest in which the smaller trees were overshadowed and yet in some measure protected by the giants.

Then came the autumn gales, and most of the tallest trees were among the first to be uprooted.

Now, from where the forest stood, we seem to look out at a different landscape. There are no broad fields like those where we ran barefoot, no briery fencerows for quail to shelter in, and no green line on tfie horizon like the one that used to mark the edge of the big woods. Everywhere in the flatland, the best farming country, are chickencoop houses in rows, in squares and circles, each house with its carport, its TV antenna, and its lady’s green cambric handkerchief of lawn. An immense concrete freeway gouges through the hills and soars on high embankments over the streams, now poisoned, where we fished for trout. It is lined equidistantly with toy-sized cars, all drawn by hidden wires to the shopping center, where they stand in equidistant rows. From a hillside we watch their passengers go streaming into the supermarket, not one by one, but cluster by tight cluster, and we wonder whether they are speaking in a strange language. There must be giants among them, but distance makes them all look smaller than the men and women we knew.