Here are some things we know about William Shakespeare. He was born in April of 1564 in Stratford-upon-Avon. His father, John, was a leatherworker who held several municipal offices in their hometown, including burgess, alderman, and high bailiff. William married a woman named Anne Hathaway who was pregnant on their wedding day in November 1585, a common occurrence at the time. Their first child was a daughter, Susanna; they then had twins, Hamnet (who died young) and Judith. At some point, William made his way to London, where he became an actor and shareholder in the Globe Theatre. We know the William Shakespeare of Stratford is the same William Shakespeare of the theater in London because in 1596 he renewed his father’s previously unsuccessful application for a coat of arms and the title of gentleman, and it was granted sometime in the next couple of years. In 1602, a list of people whose coats of arms were perhaps too generously bestowed was drawn up by the York Herald, and the list included a sketch of the Shakespeare coat of arms attributed to “Shakespear ye Player by Garter.” Shakespeare of Stratford’s last will and testament also includes a bequest to his partners and fellow actors at the Globe.

We also know that William Shakespeare wrote plays and poetry. During his life, over a dozen plays were published with Shakespeare as the attributed writer, as were his poems “The Rape of Lucrece,” “Venus and Adonis,” and “The Phoenix and the Turtle,” as well as his sonnets. Documents from the time list him as the writer of additional plays that were not published with his name on them (publishing a play without a credited author was a common practice). The company in which Shakespeare was a shareholder and actor performed these plays. In a set of popular satires called the Parnassus Plays, performed between 1598 and 1602, Shakespeare was identified as an actor-poet, quoted frequently, and mocked mercilessly. In 1623, after Shakespeare’s death, his plays were collected by people who knew him into an omnibus called Mr. William Shakespeare’s Comedies, Histories, and Tragedies, which we generally refer to as the First Folio.

There’s quite a bit we don’t know about Shakespeare. If he kept a journal—a rare practice in his day—it has not survived. If he possessed a library, it is no longer extant. We have a half-dozen odd, scribbled signatures which he may or may not have scrawled himself, and one passage of the collaboratively written Sir Thomas More that may—emphasis on may—be written in his hand. There are several years—usually referred to as “the lost years”—in which there’s no documentary evidence of where he lived or what he was doing. The list of lacunae goes on and on. Some of them can be filled in with reasonable confidence, but not certainty. We don’t know if Shakespeare was educated, for instance, but he likely went to the local grammar school in Stratford-upon-Avon because his father’s position in town would’ve allowed him to educate his children, the curricula of those grammar schools were unified, and traces of that education are abundant in his plays. I have my own answers to many of the questions people have about Shakespeare’s life, but they are based, as everyone else’s are, on a mixture of evidence, interpretation, inference, and my own autobiography.

The gaps in the record, and the appeal of coming up with those answers, have caused the birth of two different cottage industries, both of which seek to explain the remarkable achievements of the mysterious William Shakespeare. The first is the Shakespeare Biographical Complex, which churns out biographies of Shakespeare for the general reader that are filled with wild imaginative leaps. The most prominent of these is Stephen Greenblatt’s openly speculative Will in the World: How Shakespeare Became Shakespeare, which is as delightful to read as it is conjectural in its scholarship. Will in the World is a bestseller, and award-bedecked, and if you wish to learn about England during the life of Shakespeare, it’s not a bad place to start. But in terms of the Bard himself, the book is a house of cards in which every leaning laminated rectangle is printed with the word “maybe.”

The second is the Shakespeare Truther community. To these “anti-Stratfordians,” the various gaps in Shakespeare’s biography have an obvious explanation: William Shakespeare did not write the plays attributed to him. Someone else must have. None of their evidence is very persuasive; much of it does not rise to the standard of evidence at all. This has led the broader Shakespeare scholarship community to treat the field of Shakespeare Trutherism with hostility and contempt.

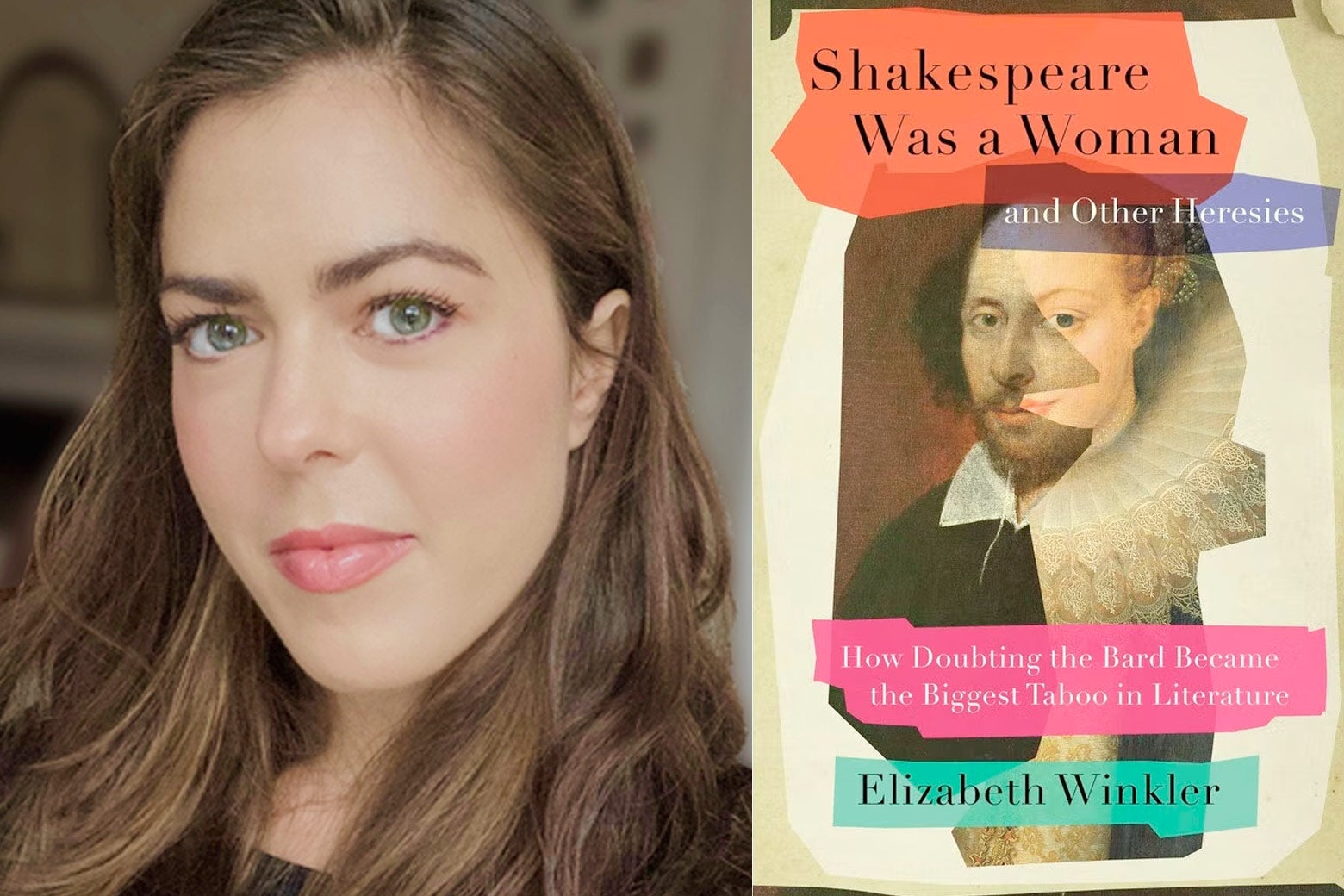

You can see the truthers’ response to that contempt in the title of Elizabeth Winkler’s Shakespeare Was a Woman and Other Heresies. Winkler wears “heresies” as a badge of honor, and that’s what makes reviewing her book so tricky. Tear it apart, and your vicious pan becomes yet another piece of evidence that Shakespeare Truthers must be on to something. Treat it calmly and even-handedly while still making clear what its problems are, and you risk legitimizing its claims as worth debating. Refuse the assignment and not only might you disappoint your editor, but you allow the book to have the last word.

Beginning with the case against Shakespeare, Winkler speaks to various truthers about their alternate candidates for authorship, laying out the “evidence” for the reader. She also attempts to speak to Shakespeare scholars, but most will not talk to her. Those who do get subjected to a third degree that stands in sharp contrast to the treatment of her other subjects. The most uncomfortable of these exchanges occurs when Winkler interrogates 90-year-old Stanley Wells, the honorary president of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust in Stratford-upon-Avon, about a book he wrote several years ago. She uses his continued protestations that he cannot remember the sources she is talking about to dismiss him as “a witness” she is cross-examining “who kept claiming amnesia.” Winkler writes, “It occurred to me that it was possible he didn’t know these allusions because he didn’t take criticism of his position seriously enough to have thoroughly studied the evidence.” That’s certainly one interpretation, though hardly the one I would reach for if my target were nearly a century old.

The source that she’s most curious about in this conversation is a narrative poem published in Shakespeare’s day in pamphlet form called “Willobie His Avisa.” Winkler’s treatment of it is a good lesson in her methods. She refers to “Willobie” as a “strange, pseudonymous pamphlet” that also contains the first explicit mention of Shakespeare. There are also characters in the poem named “W.S.” and “H.W.,” leading “scholars” to note “that the initials match those of William Shakespeare and Henry Wriothesley.” Wriothesley is better known as the Earl of Southampton, the person to whom Shakespeare dedicated his two narrative poems. The problem is that H.W. also fits the name “Henry Willobie,” who just happens to be the named author of “Willobie His Avisa,” the pseudonymity of whom is actually a matter of scholarly debate. While to most of us, a poem explicitly mentioning Shakespeare and crediting him with writing “The Rape of Lucrece” would bolster the case for Shakespeare’s authorship, to truthers the poem is suspect, because his surname is styled “Shake-speare” in the poem. “To anti-Stratfordians,” Winkler writes, “the hyphen recalls other hyphenated pseudonyms such as `Tom Tell-troth’ and `Simon Smell-knave,’ suggesting that contemporaries may have viewed the name as a pseudonym.”

This is the kind of thin evidence that Shakespeare truthers raise again and again.

Ben Jonson’s poem in tribute to Shakespeare at the beginning of the First Folio is fulsome in its praise of Shakespeare the writer, whom Jonson knew. But to truthers, its first line, in which Jonson wishes to “drawn no envy … on [Shakespeare’s] name” is the first in a series of clues that he is praising a writer who used Shakespeare as a false name. A monument to Shakespeare in Stratford-upon-Avon exhorts passersby to “read if thou canst,” which Winkler interprets as an invitation to puzzlers to “figure out its meaning”—as opposed to a banal reference to the low literacy rates of the early 17th century. The fairly straightforward monument pays tribute to Shakespeare as a writer (“all th[a]t he hath writt/ Leaves living art, but page, to serve his witt”), but to truthers, a mention in the First Folio of the monument one day “dissolving” while Shakespeare’s “workes … out-live/ Thy tomb” is another sign that it should be decoded, since “in the Renaissance, dissolve was used to mean ‘decipher,’ ‘resolve,’ or ‘figure out,’ as in the modern solve.” Sure, but in the Renaissance dissolve also meant … well, dissolve. The OED page for the word lists a plethora of meanings, all of which were active in the 17th century, and only one of which means “solve.”

The book is chock-full of this kind of stuff. If you don’t pay close attention to the “evidence” being presented, it sounds pretty good, or at least plausible. Winkler’s prose is smooth, her jokes land, her synthesis of the considerable amounts of research she’s done is gracefully rendered, and she has a keen eye for the foibles of Shakespeare biographers. But spend some time checking her work on your own and it quickly falls apart.

Winkler’s anti-Stratfordians reverse this charge. Any scholars who dismiss the more unlikely readings of the sources “must ignore the historical and cultural contexts in which the author wrote. They must cover their eyes and block their ears to allusion. They must, in short, commit literary malpractice.” Winkler inserts a tiny bit of distance from this position, refusing to claim it as her own and asking herself, “Have the scholars failed to interpret properly the sacred texts in their care?” By the end of the book, it is clear her answer is a resounding yes.

A major problem for the truther community is that in centuries of looking, it has failed to turn up any primary documentary evidence of anyone besides Shakespeare writing the works, nor any viable candidate for the “real” author. Sir Francis Bacon, one of the earliest alternates floated, was a brilliant scholar and writer, but was far too busy to have produced two plays a year. The dramatic writing of his that does survive also bears no traces of Shakespeare’s brilliance. Edward de Vere, the Earl of Oxford, died before Shakespeare’s career ended; Christopher Marlowe died near its beginning. Winkler’s contribution to the popular understanding of the authorship question was to focus on scholarship that broadens the list of candidates to include women in a piece in the Atlantic titled “Was Shakespeare a Woman?” That story’s major errors, and their correction by the Atlantic’s editors, get relitigated over the course of the book. Rather than re-relitigate this mess, it is sufficient to note that one of the major female candidates, Mary Sidney, probably knew Shakespeare (the First Folio is dedicated to her sons), but there is zero evidence that she wrote the work published under his name. The other, Emilia Bassano, is sometimes floated as a candidate for the “Dark Lady” of Shakespeare’s Sonnets, but by Winkler’s own admission, her writing “bears no obvious resemblance to Shakespeare’s.”

In Shakespeare Was a Woman, instead of claiming “Shakespeare didn’t write his plays” or “Person X wrote the plays of Shakespeare,” Winkler only makes the case for doubting the official narrative. This clever argument has a much lower evidentiary threshold; it is always easier to shoot holes in someone else’s case, particularly when the position from which you launch your attacks can be changed whenever you wish. Still, the major truthers she interviews are true believers in their cause, and through her deferential reporting, we learn exactly how flimsy their arguments are. Alexander Waugh, the book’s major champion of Oxfordianism, claims that Oxford’s early death in 1604 proves that he wrote the plays of Shakespeare because Shakespeare’s output slowed for the next few years. But while we don’t know the exact chronology of Shakespeare’s work, and some of the plays’ years of completion are unknown, the documentary record fits Shakespeare’s life. The earliest play we have public records for, Henry VI, Part 2, was registered in 1594. The last ones all emerge after 1610. We know that Cymbeline was first mentioned in 1611. Winkler claims that “The Tempest … is dated to 1610-1611 based on a 1609 letter describing a real-life shipwreck,” implying that the evidence is flimsy, but that date range exists because the earliest public record of it being performed is dated Nov. 1, 1611. Henry VIII, the play that burned down the Globe Theatre, was first performed in 1613. The only documented outlier is The Two Noble Kinsmen, the earliest recorded production of which is in 1619, after Shakespeare’s death. That play is also one that we know was co-written with John Fletcher—they’re both credited as authors in the Stationers’ Register—and thus it is possible that Fletcher, who lived until 1625, saw it through to that production.

Waugh’s case relies less on doubt about chronology and more on what he believes to be coded references to Shakespeare being Oxford. These tend toward Dan Brown territory very quickly. According to Waugh, if you look at the famous portrait of Shakespeare in the First Folio, you will see a “bright light on the forehead and the great rays coming out from his collar,” which must be references to the “great Phoebus-Apollo, the patron god, hiding behind the mask of a player.” That patron must be Oxford because he was often referred to as Apollo. He suggests, absent any evidence, that Oxford ran a kind of writers’ room as “the head of the group, and he owns, if you like, this name ‘Shakespeare.’ ” But Oxfordians like Waugh have “found” so many coded references to Shakespeare being Oxford that, if this were true, Shakespeare’s real identity would have been an open secret everybody knew, yet was never explicitly written down anywhere.

Ultimately, Shakespeare Was a Woman’s real target is less the Bard than the scholars who study him. Winkler casts doubt on their aptness to their task at the very beginning of the book. “Who has the authority to determine the truth about the past?” she asks. “Usually the answer is historians. In the case of Shakespeare, it is Shakespeare scholars, a small but highly prestigious subset of English literature professors concentrated mostly in Britain and America.” Later, she asserts that the study of English itself is a conspiracy, a replacement for religion in a secularizing society, meant to stave off the revolutionary fervor gripping France by providing “the unifying, pacifying function formerly provided by Christianity.” This new church required a new Christ in the person of William Shakespeare, who was already undergoing deification within Victorian society. These religious metaphors run throughout the book. Shakespeare scholars are a group of priestly fanatics in Winkler’s metaphors, forever threatening to cast out the “heretics” who see the world differently. But while there are certainly dogmatists in Shakespeare studies, as there are in any field, our understanding of Shakespeare is constantly evolving. As Winkler herself points out, in 1986, the idea that Shakespeare collaborated with other playwrights was highly controversial; now it is a mainstream view. To Winkler, of course, this doesn’t show the open-mindedness of the field to new evidence, but rather “betrays an extraordinary cognitive dissonance. While scholars insist there is no authorship debate, they engage in their own authorship debate.”

And this is why trutherism is so pernicious. While doubting Shakespeare’s authorship isn’t nearly as dangerous as climate change denial, or anti-vax beliefs, or questioning Obama’s citizenship, the rhetoric and strategies of all of these forms of trutherism are quite similar: Question the qualifications of the authorities. State some assertions we can all agree with, like “We don’t know much about the life of Shakespeare,” or “Some people who have been vaccinated against COVID-19 die from the disease.” Ask an escalating series of questions about the consensus view, shifting ground whenever you would lose the point being debated. Deploy shaky evidence that requires tendentious interpretation. Claim that evidence that disproves your theory in fact supports it. Needle those in power who refuse to engage with you. Use the contempt with which your position is treated as evidence that you must be on to something. Whenever possible, fall back on saying you’re just asking questions.

Trutherism abuses the liberal public sphere by using the values of liberal discourse—rational hearing of evidence, open-mindedness, fair-minded skepticism about one’s own certainties, etc.—against it. Once the opposition tires of this treatment and refuses to engage in debate any longer, the truther can then declare victory, and paint the opposition as religious fanatics who are closed-minded and scared of facing the truth.

The final Shakespeare scholar Winkler confronts is Marjorie Garber. Like me, Winkler is a huge fan of Garber’s masterful Shakespeare After All, a collection of essays on Shakespeare’s plays. Garber refuses to discuss Shakespeare’s biography or the authorship question, because to her, “Shakespeare is a concept—and a construct—rather than an author.” Garber’s own book on the subject, Shakespeare’s Ghost Writers, focuses on deconstructing the longing for stable authorship rather than sifting through historical evidence. When Winkler asks Garber if she is certain Shakespeare wrote Shakespeare, Garber responds, “I’m not a biographical scholar and I don’t make biographical claims.” When asked if that means she isn’t a Stratfordian, Garber responds “I’m a Shakespearean … That’s what I am. I’m interested in the plays.”

Winkler is flummoxed to meet a Shakespeare scholar who does not care about authorship, but most Shakespeare scholars are not particularly focused on the authorship question. It has been asked and answered. Sure, the most famous authorities love churning out their biographies, but most of the field remains focused on the far richer subject of Shakespeare’s work and its relationship to the world in which he lived. That area of study is nearly infinite in depth, and boundless in its rewards. The plays remain complex, confounding, impossible achievements (and, let’s be honest, some clunkers). They are a great gift to the world, waiting for each generation to receive it. Their author has, whether by design or by accident, been reduced to a shadow lurking behind the work. Unless some new evidence arises, let us leave him there, offstage in the dark, and focus on what really matters.